What it was…

Nicole Marzan, 43, remembers her Friday nights at The Tunnel vividly.

She can recall Funkmaster Flex in the DJ booth, moving the crowd with his characteristically bombastic bravado, flanked by hip hop’s hottest and coolest in New York City. Drinks flowing. Music thumping. Lights flashing. Bodies joyously moving almost to the point of sweaty exhaustion.

“The energy was unmatched,” Marzan says smilingly about the now shuttered Manhattan nightclub that was dubbed as the nucleus of hip hop where music executives, high powered CEOs and it girls all congregated on weekends.

“You went there to dance and potentially almost get into a fight. You knew to wear jeans and sneakers instead of a miniskirt and heels because it wasn’t a place where a woman can be dainty. You came to connect with your peers. Lose yourself in the music. To leave it all on the dance floor.”

It was a religious experience for the then 19-year-old Nicole, a bright-eyed aspiring celebrity publicist that always knew where the who’s who frequented in the city. Nearly two decades later, that fact hasn’t changed, as she’s a seasoned PR specialist who’s worked with everyone from Swizz Beatz to companies like LVMH (Louis Vuitton, Moet, Hennessy). Now she’s leading brand public relations efforts at the renowned Cashmere Agency working on Suntory’s tequila portfolio. Essentially, she knows the nightlife business like the back of her hand.

“Everything is different and not necessarily in a good way,” she tells. “For many of us, it feels like the soul has been sucked out of nightlife.”

What it is…

A recent TikTok video recently went viral because of a simple question: what did the club used to be like?

In response, app users answered in droves, likening the club experience in the early aughts and 2010s to a real life enactment of Nelly’s Hot In Here, as referenced in the TikTok video.

“I’ll tell you exactly what the club was like,” explains popular TikTok user RaeShanda Lias in response to the original question. Lias, who says she graduated high school in 1999, implores “I want you to close your eyes and picture this, okay? You got Jersey dresses and high heel Timberland boots. It smells like Pump It Up and [Bath & Body Works] Japanese Cherry Blossom.”

She continues: “We’re throwing ass left and right. We’re standing on tables and chairs, fighting. You stepped on my shoe. Oh, yes, we party in the club. We danced all night.”

Thousands of commenters affirmed this take of the party-going experience back then, a stark juxtaposition to the staidness younger Gen Z club patrons describe now.

The longing feelings many young adults feel for the heyday of clubbing underscores a recent Meta-Gallup survey that found 27% of people ages 19 to 29 feel deep loneliness. The first generation to be raised with social media, the internet has essentially been their primary form of socialization and human connectedness.

The club, which was was once an almost euphoric outlet of sorts, has taken on a new form for many.

“Going to the club is a chore now,” J. Mulan tells ESSENCE. She is a well known Houston-based influencer who frequently promotes and curates club events across the country. “If you can’t hop out of car service in full glam and luxury labels on from head to toe then you’re not doing it right. If you don’t have a section with bottle service with buckets full of whatever the hottest liquor brand is at the moment, you might as well stay home. And then when you get there, you’re not dancing for real because you’re too busy recording yourself on your phone. If it’s not posted then it didn’t happen. That’s why when you look at club layouts nowadays, there’s no dance floor, only sections.”

Despite still being in her twenties, J. Mulan, 29, says the club scene has drastically evolved in the time she’s been in it. She began her event promotion journey in 2014 when she organized a club appearance for the then burgeoning rapper Travis Scott.

“I know it’s been ten years but it feels like a completely different universe—the entire business model for nightlife has been flipped on its head. Back then, you’d be able to bring people out with just an underground artist’s name on the flyer. You didn’t have major brands in the club all competing for consumer dollars, especially in Houston where stripper culture was dominating. Nowadays celebrities are commanding five or sometimes six-figure checks to come to clubs when before, they would come to just connect with their fans in a real way. A lot of promoters and venues can’t afford that, that’s why you’re seeing less celebrity names popping up for club appearances. This was before the city started leaning towards the more Atlanta type of partying.”

She’s referring to the now popularized vibe dining style of clubbing, a term coined by nightlife insiders in which restaurants incorporate elements of club culture including louder music, bottle service and hookah smoking. One of Atlanta’s pioneers in the nightlife industry since the 90s, William Platt, agrees with the shift, which is why he’s set his sights on branching beyond the space.

The latest concept Platt developed is The B.A.N.K—a large-scale event space that can be rented—located in west Atlanta that he hopes will economically revitalize underserved parts of the city.

“Being in nightlife ain’t easy, especially if you’re in it for the wrong reasons,” Platt tells ESSENCE. “I’ve moved past the fast money-making part of being in nightlife. We kind of started a specific type of partying down here in Atlanta where the customer came first—southern hospitality set us apart from every other major city in the country. Now, we’ve kinda’ earned the worst reputation for customer service because everybody, even some of the workers in the venue think they’re a star.”

Steve Rogers, a Houston-based nightlife entrepreneur that owns a number of popular venues including Prospect Park, Bar 5015, and The Rockhouse, says the events business is even trickier now because of a fundamental physiological shift.

“People’s attention spans are so short that it’s hard to understand what people need to have fun nowadays, particularly for that target demo for clubs {which is around 21-32},” Rogers tells ESSENCE. “Dj’s will play a few seconds of a hit song, get the crowd hyped and then go to something else no one wants to hear because they think they need to constantly switch things up instead of riding the rhythm of what the audience responds well to. There’s a lot of that happening now which is unfortunate because it’s our job to set the right tone.”

However, Christopher ‘Sigma Chris’ Davis, a popular Chicago-based event producer, says the negative shift in Black nightlife isn’t all on the curators.

“We’re responding to what we get from the customer,” he tells ESSENCE. Davis says he owes a big part of his success to a high level of communicativeness he has with his consumer base. He often takes to Instagram and X to keep event-goers abreast of any changes to his team, policies or even public affairs that may affect his events.

“I’ve been honest in the past about how racism has impacted Black people that want to go out in Chicago,” he shares, admitting that some racial stereotypes have informed the way he plans his events at times. “I vet my crowd because if I don’t, people’s safety could be put in jeopardy.”

He explains that because of past violence, he uses social media to perform cursory background checks on RSVPers of his events. He also ensures security is situated across multiple checkpoints in the venues. This can make for long lines at the door, a turn-off for some partygoers who wind up waiting upwards of an hour or more before gaining entry.

Chaz Maull, a freelance party planner who has created programming for the Soho House agrees that event producers have to be more discerning with their guest lists, particularly in recent years. “I think the pandemic has shifted the way we party and who we party with—we’re still getting used to being around each other, so I think we need to be careful with the way we bring people together.”

Davis says of his strict policies: “I wouldn’t have to do this if there weren’t for fights, scuffles or even shootings at other events. Certain things have to stop. People have lost their lives at parties. That’s crazy. That’s why we don’t see as many Black-owned lounges and clubs or even as many Black-focused pop-up parties happening. They haven’t earned the trust of venue owners yet—that something bad won’t happen in the space they own. And if you don’t earn that trust, you end up paying for it on the back end.”

Lisa Gardner, Executive Director of the Illinois Liquor Control Commission, says crowd control can immensely impact nightlife operators’ liquor licensing.

“Business owners can lose their license depending on the type of activities that happen there {even if it’s not their fault},” Gardner explains. “If there’s a shooting inside or outside, it can just be coincidentally in a parking lot adjacent to it but that impacts the business. If there’s a lot of noise and congestion, that’s why bars and certain nightclubs are required to have zoning because they’re supposed to move the traffic. When people start congregating, that’s noise and then you have to contend with neighbors’ complaints and subsequent fines” which can ultimately drive up the operational costs for party producers.

Noise pollution, as explained in The Atlantic’s September 2022 issue, is often vehemently opposed by non-Black and Brown affluent groups.

The outlet states: In 1991, the NYPD launched Operation Soundtrap, a campaign in which cops would trawl streets—often in majority-Black-and-brown communities—hunting for and confiscating cars with enhanced stereo systems. (“If they don’t turn down the volume, we’ll turn off their ignition,” the chief of the police department vowed.) When Rudy Giuliani became mayor in 1994, he used a cabaret-license law to force clubs out of gentrifying neighborhoods like the Lower East Side and Chelsea. The battle against nightlife continued during the Bloomberg years. New York was effectively codifying an elite sonic aesthetic: the systemic elevation of quiet over noise.

New York and LA-based event producer Venus Cuffs attests that race and gender plays a huge role in how successful one can be in the nightlife business.

“There are so many hurdles Black event producers have to overcome before the event even gets off the ground that people on the outside have no idea about,” she says. “I see people complaining all the time about how nightlife isn’t fun anymore, but I don’t see anybody talking about the business challenges we face.”

She points to the other ‘isms, colorism and sexism in particular, as the main culprits Black women event producers like her regularly contend with.

“Nightlife, it’s a very shallow industry,” she says. “It’s not super body positive—I’m not skinny, I’m not light-skinned, I’m not biracial or racially ambiguous. When people deal with me, I have to doubly prove myself.”

A byproduct of her otherdness means not coming by funding easily, which affects the quality of the events she’s able to produce.

“When you’re not the physical type people want from a Black woman–fair skinned, thin, certain hair type—it can be hard to be in a perceived position of any power. I’m not backed by a bunch of men that are funding me.” According to recent data, more than 70% of night club leadership positions belong to men, underscoring the homogeneity in the space.

Venus Cuffs also points out that inflation is affecting how event producers are planning their events as operations become more expensive and people are starting to go out less.

“It’s a tighter squeeze on the amount of money going around because of the economy,” she says. “Live entertainment, dance parties, shows, they’re all slowing down in major cities because there’s less capital circulating. People are drinking less which affects everything in the nightlife business.”

Patrick Richards, an executive at LVMH that oversees Moet Hennessy’s high energy division for the Southeast region (Florida, Texas, and Georgia) says the prestige brand has readjusted the way they connect with consumers in recent years.

“I think one of my biggest observations lately is that the competition within the spirits business is being forced to become more innovative. I noticed that right now we’re in a time where I think consumer spending is down a little bit. Whether people admit it or not, we are probably in a bit of a recession. Number two, I think crypto, Bitcoin, NFT, all these booms along with COVID relief, people were getting money and spending money. All that money is gone now. The days of people just buying those huge bottle parades—25 bottles and 30 bottles in one sitting. We don’t see that anymore.”

Venus Cuffs attests to this.

“Everyone’s starting to get a little more cutthroat, a little more competitive,” she tells ESSENCE. “And more people, particularly Black people are competing with one another more than ever instead of working together, and that just hurts the consumer in the long run. There’s less money to spend on theming, quality Djs, beautiful venues, thus translating in people just sitting around not having any fun. They’re too busy perpetuating a certain look or being on their phones to actually enjoy themselves. But you know who’s doing it right? Queer event curators.”

What we want it to be again…

Jameel Rainey, founder of Meel Ticket Ent., a Chicago-based company that produces inclusive events across the country began throwing pop-up parties in 2023 after noticing a lack of spaces for Black gay men and allies to enjoy themselves. Alongside his business partners James Ellsberry and Laqwan Johnson, they’ve curated more than a dozen well-attended events that have garnered immense praise.

“I can’t tell you how many times I’ve been thanked by people for launching the company and wanting to create a safe space for everybody to be able to have fun at,” Rainey tells ESSENCE.

“They got that in Atlanta, they got that in Houston, they got it in DC,” Johnson says. “The gays, and the girls and the straight men, they all party together as one, but this stigma in Chicago is like, you can’t be in our community and party with straight people. It’s terrible. It just makes everything separated and all over the place with nightlife,” he explains, pointing to the segregative state of Chicago, a city that has long been named one of the most racially divisive in the country.

Rainey also points out that his team takes great care in creating an environment where people can easily interact with one another.

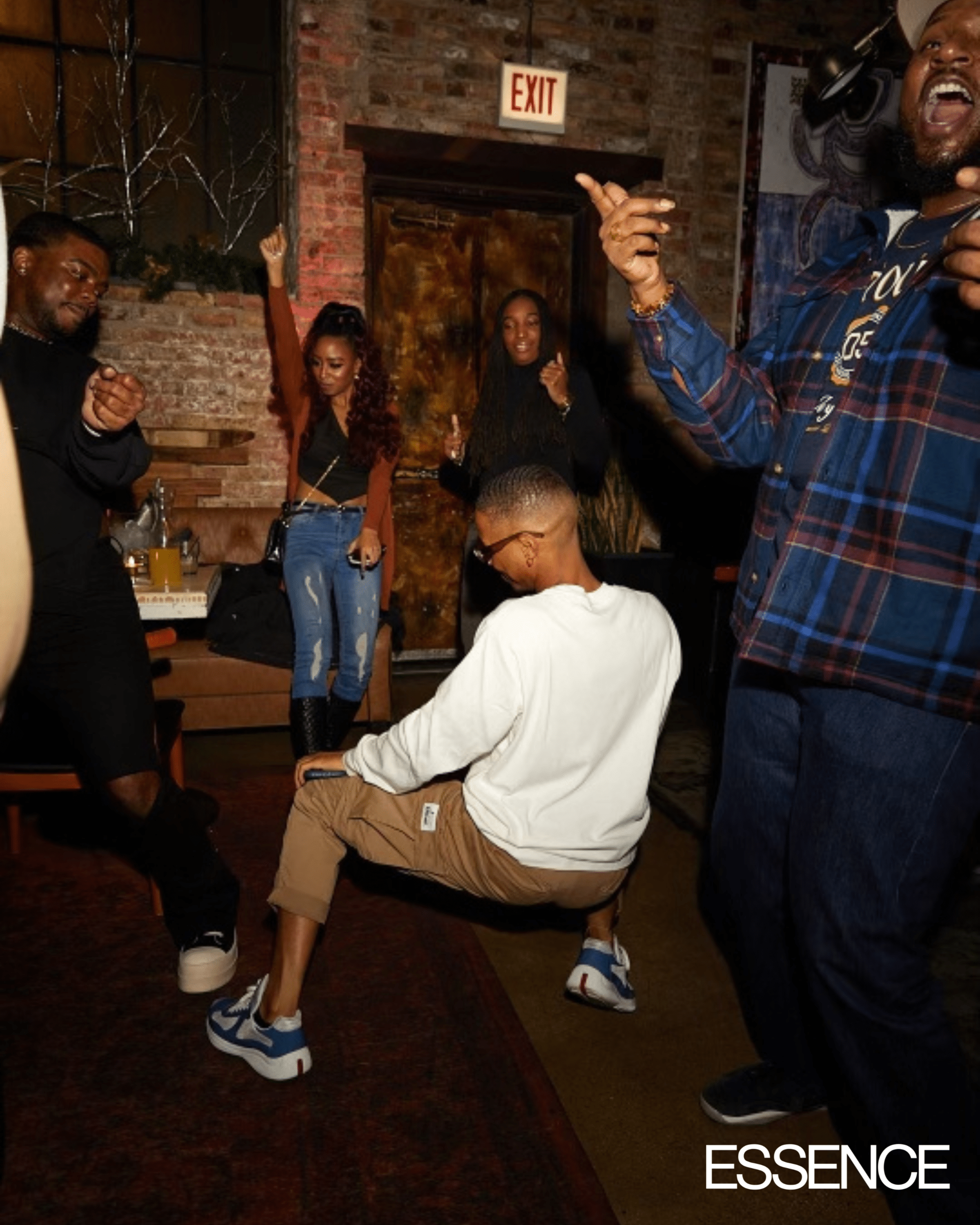

“We try to select venues with a dance floor, some seating is needed ofcourse but ultimately we want people to move around, bump into each other a little bit, be free, strike up conversations, actually see one another under the club lights. We want to foster a new wave of life-long memories for younger generations to have like we as millennials were able to create in our early twenties. We just want to make nightlife fun again.”

This interview has been edited for clarity and brevity.