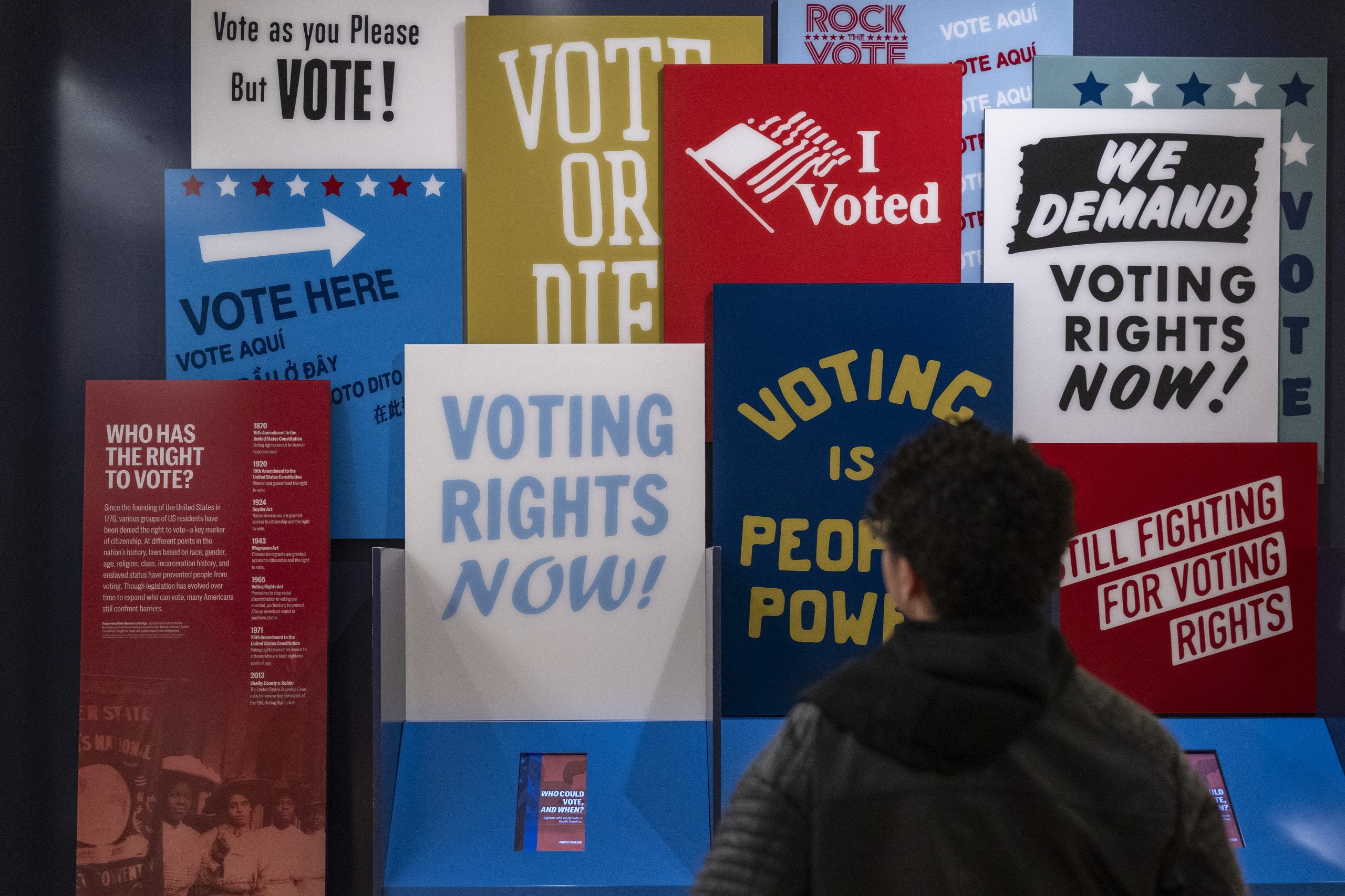

Harrowing footage from the Civil Rights era—courageous protesters demanding their right to vote, met with batons and tear gas—still haunts the American conscience.

Those searing images of state-sponsored violence captured the danger Black people faced in exercising their constitutional rights before the 1965 Voting Rights Act.

Janai Nelson, President and Director-Counsel of theLegal Defense Fund, explains that the obstacles weren’t just social but were written into law.

“When we attempted to exercisea right to vote in many states, we were doing that at great risk to our lives, at great risk to our livelihoods… literacy tests, Grandfather clauses—all manner of instruments were designed intentionally and quite surgically to keep Black people out of the ballot box.”

The impact of these efforts was unmistakable. Before the act—and the relentless voter registration campaigns that preceded it, just23% of Black Americans were registered to vote. By 1969, it was 61%. In Mississippi, where voter suppression was especially egregious, registration jumped fromunder 7% in 1965 to 59% by 1968.

It also caused a seismic shift in Black political leadership. Today, there are over 10,000 Black elected officials nationwide, up from just 300 in 1965.“That has made a significant difference in terms of how policy is shaped, in terms of how leadership is viewed. And it’s brought us much closer to this ideal of multiracial democracy,” said Nelson.

However, not all progress was sustained. The Supreme Court’s 2013 decision in Shelby County v. Holder weakened voting protections. Chief JusticeJohn Roberts wrote that the country had changed so protections were no longer needed.

Ironically, the very changes he cited were the result of preclearance—a provision that required states with histories of racial discrimination—largely in the South—to get federal approval before changing voting laws. That safeguard was eliminated and voter suppression laws have proliferated ever since. Since that ruling, dozens of states have passed laws that restrict access to the ballot, from voter ID requirements to polling place closures and gerrymandering.

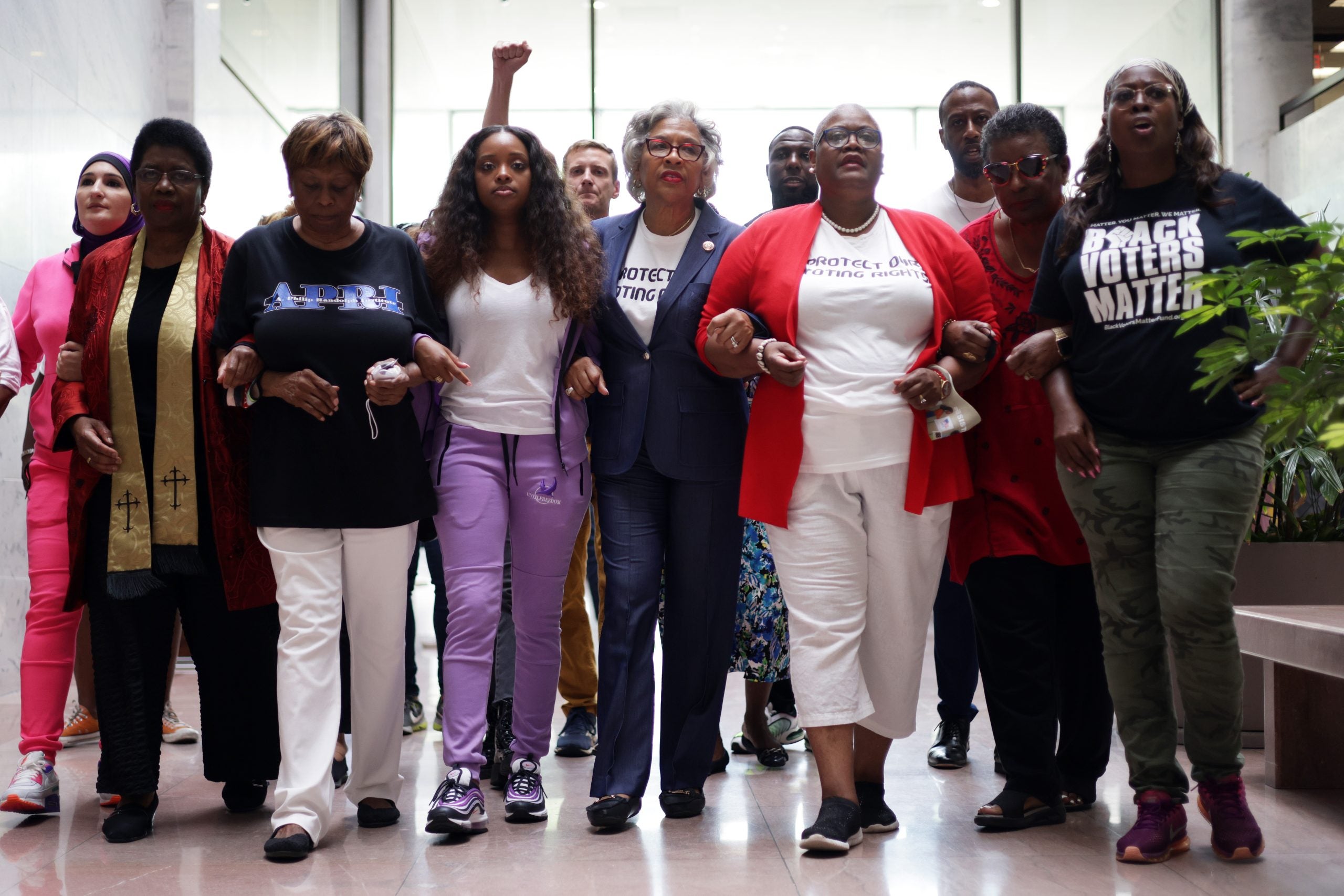

“Once you strip out preclearance… it takes the teeth away from voting rights. This wasn’t about something no longer needed—this was a wholesale attack to undermine democracy,” said veteran organizer LaTosha Brown, co-founder ofBlack Voters Matter.

Brown described with alarm how the erosion of voting rights is unraveling democracy itself. “Across the board, we’re seeing the grab of power. We’re seeing the undermining of citizens’ rights. We’re seeing the suspension of habeas corpus.”

For these reasons, civil rights groups, lawyers and grassroots activists are fiercely opposing these tactics, just as they did more than 60 years ago.

The Legal Defense Fund channels the spirit of its founder, Thurgood Marshall, to challenge voter suppression laws nationwide. Nelson successfully argued in Veasey v. Abbott that Texas’ voter ID laws discriminated against Black voters during Trump’s first administration and stands ready to bring lawsuits against new ones.

LDF also backs every reauthorization of the Voting Rights Act (which occurs every 25 years) and supports the John R. Lewis Voting Rights Advancement Act, reintroduced last week by Senator Raphael Warnock and others. The bill would restore federal preclearance and strengthen voter protections.

Meanwhile, LDF is spearheading voting rights protections at the state level. Colorado, Connecticut, Minnesota and New York have passed their own Voting Rights Acts. Other states, including Alabama, Florida, and Texas, have introduced similar bills.

“I do think the growing realization that our democracy is rigged is going to have more and more Americans take a look at what has been done in the past to protect our democracy, what tools are being attacked and hopefully to embrace them, because they recognize… all of us having unfettered access to the right to vote [is] a better system than the one we have, where all votes are being manipulated,” said Nelson.

At the same time, outreach and organizing at the community level remain just as essential.

In addition to litigation,the Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights Under Law partners with grassroots groups to guide its election protection work. Theirelection protection coalition includes over 300 national organizations whose volunteers assist at all levels of the voting process, from registration to casting ballots. They also run a national election protectionhotline.’

“The organizers are the ones that are helping us, oftentimes, to get an early heads up on where a litigative response might be necessary, or where more public education is going to be crucial to ensure that people know what they need to know in order to enforce their rights” said Shaylyn Cochran, Deputy Director of the Lawyers’ Committee.

In addition, Brown draws on Black traditions of culture and collectivism to mobilize communities.

“To combat the culture of fear requires collectivism,” she said.

During the “We Fight Back” bus tour, which mobilized Black voters in 12 states during the last presidential election, the red, black and green buses—emblazoned with Black power fists—became rolling symbols of defiance and celebration.

“We are tapping into Black joy, because Black joy is the antidote to white fear.” Music, too, is a key organizing tool. It’s used on the bus and is part of all their voter participation efforts.

“We’ve always used music and song and relationship and oration and organizing,” Brown said. “They used freedom songs…they used the idea of really gathering people and tapping into spirit and faith…They used their bodies to create a sense of belonging and a protection of everybody. We do the same thing.”

Despite the formidable challenges Black voters still face, Brown is inspired by the strength and resiliency of those who came before her. Her grandparents, Alabama natives, couldn’t vote until they were nearly 60. Her 91-year-old aunt wasn’t allowed to sit at the front of the bus—yet she lived to see her niece own buses.

“I’m able to own a bus because those folks got on buses that were sometimes bombed,” she said.

That legacy is why she believes in the power of the next generation to dream bigger. “The Voting Rights Act was a vehicle to actually move us towards the expression of the full humanity of Black citizens and all citizens in this country,” Brown said.

“Young people need to build on that and make it better. What is your radical reimagining of the country—and how do we get there?”