My first trip to Accra, Ghana, was full of emotion. From the moment I stepped off the plane and heard “Welcome home,” I felt the ancestral tug so many had described. I knew this trip would be more than just a photo dump or an Instagram reel.

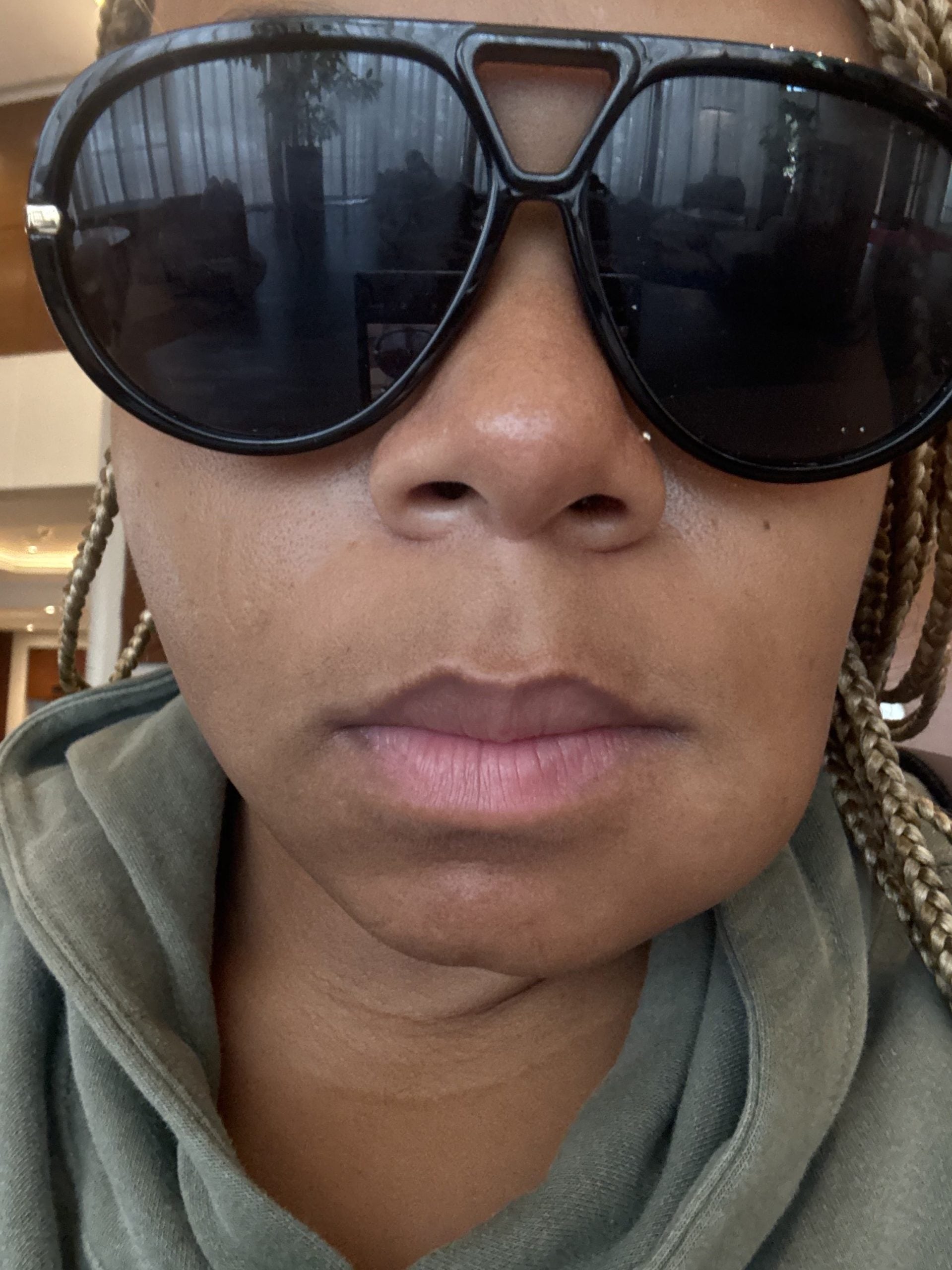

My visit was to learn about Accra’s thriving businesses and vibrant culture — not to end up in the emergency room. But overnight, a nagging toothache developed into a full-blown abscess, swelling my face to twice its normal size. Once the panic faded, a new fear set in: I’d have to go to the ER. I hate to admit my first thoughts were shaped by Western media and colonization-influenced assumptions — that healthcare in Africa would be inadequate and that I needed to fly back to the U.S.

I was quickly proven wrong.

At Ridge Medical Center, I was checked in within minutes. Staff walked me through the insurance verification and care procedures, as I wasn’t a citizen. As I waited, I noticed a fully stocked on-site pharmacy, a spotless facility, and posters advertising community clinic days offering free screenings, from eye exams to diabetic checks.

The care itself rivaled what I’ve received in any American hospital. I underwent sterile lab work, received care from an attending physician, and had continuous bedside supervision.

To my surprise, my case was reviewed by a dentist, a dental surgeon, a general surgeon, and a general practitioner, each of whom came to speak with me and offered input, as I wouldn’t be in Ghana for a follow-up.

As a Black woman in America, where medical encounters can feel daunting — and too often dangerous — that level of coordinated, intentional care was eye-opening.

Back home, I followed up with my U.S. physician and noticed stark contrasts. Ghanaian care favored lower narcotic doses over longer periods, while American prescriptions relied on higher doses more frequently. The attentiveness and physical engagement also differed. The experience challenged my biases about healthcare outside of the U.S., specifically on the Continent. Africa is too often portrayed as a place of scarcity and struggle. What I encountered in Accra was the opposite: a story of progress, skill, and patient-centered care.

“The reality is that in Africa, while healthcare quality varies widely across countries, there are excellent public and private hospitals and clinics with internationally recognized accreditation. These facilities often have highly trained doctors and modern equipment,” says Emmanuel Gyimah Amankwa, BSC, MBChB, MGCS, MWACS, MPH, Chief Executive Officer of Ridge Medical Center, when asked about misconceptions surrounding African healthcare systems. Amankwa explained why this perception imbalance persists.

“International media outlets tend to focus on crisis-driven stories such as outbreaks, shortages, or humanitarian disasters because those narratives attract attention and evoke emotion. Meanwhile, stories about local innovation like Ghana’s use of drones for medical deliveries or digital health records get far less global airtime.”

He adds, “During the colonial period, Africa was often portrayed as a place of deficiency needing ‘saving’ or ‘modernization’ from outside powers. That framing still lingers in many global institutions and aid narratives. As a result, progress is seen as something given to African systems, not driven by them.”

Though he acknowledged that “there are still areas with severe healthcare challenges, limited infrastructure, workforce shortages, and supply gaps,” he noted that many people still imagine outdated, 1990s-era systems. These misconceptions of “unsterile conditions, outdated technology, and inadequate care” extend beyond Africa to many developing nations where people of color make up the majority.

Travel photographer and content creator Carey Bradshaw has seen this firsthand. His travels in 2023 took him to Saigon, Vietnam, and Kingston, Jamaica, where he ended up in emergency rooms for unrelated issues. Across both visits, he received MRIs, X-rays, multiple tests, and blood work. The difference? The cost.

His ER visit in Vietnam was $260. In Jamaica, a private hospital charged $400. Both facilities treated him without insurance, provided medication, and offered what he described as a level of care he’s “never been privy to in the States.”

“It was the human part that stood out,” Bradshaw says. “The doctors didn’t just check boxes; they were genuinely concerned. They asked smart questions, connected the dots, and actually tried to solve the problem instead of rushing me through. In both cases, once they diagnosed me, they gave me the medication right there on the spot. I didn’t have to make a separate trip to a pharmacy or wait for a prescription to be filled. It was a mix of professionalism and compassion that honestly humbled me. I realized how much I had underestimated the quality of care outside the U.S.”

Amankwa says this kind of underestimation is common. “With many assuming that international hospitals marketed to expats are the only acceptable places for care, they end up being overcharged or having unnecessary treatments,” he says. “It reinforces the false idea that ‘local’ equals ‘unsafe,’ and deepens inequities between expat and local patients.”

These biases can lead travelers to delay care — sometimes with serious consequences.

That was nearly the case for Bonita Jackson, a long-time expat living with PCOS. Out of fear of subpar treatment, she often ignored pain flare-ups. A severe episode in Saudi Arabia finally sent her to the ER, where she was seen by a Sudanese doctor who was assigned her case due to their shared African roots. For Jackson, being seen and understood, rather than dismissed, was transformative.

“Doctors take their time. They explain things. They don’t just treat the symptom; they talk about the cause,” she says, adding that she’s encountered physicians who “lead with care before cost.”

She continues, “There’s a real sense of humanity in the way they treat you. They look at you as a person, not a paycheck. Even in moments when the language barrier was there, compassion filled the gap. Whether it was a nurse bringing me hot tea in China, or a doctor in Iraq checking on me the next day just to make sure I was okay, those gestures stuck with me. I was surprised — not because I expected bad care, but because what I received went far beyond what I imagined. It reminded me that professionalism and kindness speak a universal language.”

That same compassion defined Maleeka Hollaway’s experience in Bali, where she fell ill at 20 weeks pregnant with “Bali Belly.” A doctor and nurse visited her hotel to provide care, a level of personal attention she had never received in the U.S.

“It was just refreshing, actually, to sit there and talk to a doctor, [have them] ask me about myself, the pregnancy, how I’m feeling, ask me questions about my life, like that was a rewarding experience. Extremely professional,” she says. Hollaway’s experience also echoed Jackson’s, a blend of natural remedies and holistic consideration of mental and environmental wellness.

These positive experiences highlight something deeper. For many Black people, healthcare is not just physical — it’s emotional. The relationship between Black individuals and medicine remains a complex, nuanced conversation, built on histories of exploitation, neglect, and systemic bias. Jackson admits she was sometimes ignored abroad until people realized she was American.

Still, in many of these countries, where Black and brown professionals lead the care, medicine feels more human-centered and community-rooted. Patients are treated as partners in their healing, not as numbers on a chart. While no system is perfect — many of these developing countries are facing unavoidable funding shortages and infrastructure gaps — these healthcare models embody a cultural truth that care is relational, not transactional.

For Black travelers and expats, walking into a clinic and being met with dignity, empathy, and time can be the difference between life and death.