It’s no secret that 2000s fashion has been in heavy rotation for some time now. According to Pinterest reports, Y2K styling trends have been dominating searches for several years, with both Gen Z and millennials reaching backwards to reshape their closets. As we tend to think fondly of the moment filled with bright and colorful aesthetics, graphic tees, butterfly clips, and trucker hats, somehow we collectively decided on where our nostalgic hearts had to draw a line in the fashion time capsule.

Between 2007 and 2009, we started to sense a shift towards styling that felt more wild, more risky, and sometimes downright obnoxious, bringing to mind trends that for whatever reasons have yet to resurface. So while the “Swag Era” might not be the first place you turn to (yet) for fashion inspiration, it does deserve a second look.

Even if your lime green leopard print skinnies and Obey tees are buried deep in the depths of your closet, stepping back through that threshold might uncover more than your old, tacky but favorite outfits. Believe it or not, there might be a deeper story here about youth, rebellion, and the cultural and political mood of the 2010s.

As far as fashion history goes, the “Swag Era” is generally overlooked. Maybe it’s because not enough time has passed for critics to consider it worthy of deeper analysis. It could also be due to the styles being dismissed as loud, gaudy, or unserious. Unlike most fashion eras neatly boxed by decade, like, for instance, the 1990s or the 1980s, the “Swag Era” resists that structure. Instead, it straddles two decades and unfolds over a compressed span of four to six years, roughly between 2008 and 2014, making it harder to pin down but no less culturally significant.

According to Cydni M. Robertson, a fashion historian and the assistant professor of fashion merchandising at Indiana University Bloomington, it might be too soon for this era to be appreciated. “For today’s youth, the 2000s and 2010s now represent the decades that their aunties and uncles were seen as ‘cool’. For the current aunties and “uncs” [or millennials], the ‘Swag Era’ apparel can reflect a time that maybe is no longer relevant to the adult versions of who we are.”

Most of you reading this will be able to place yourselves in the middle of your own memories. But if you can’t recall, (or have blocked out all memory of it), picture this: Nicki Minaj was at her peak with the release of “Pink Friday.” The entire Young Money crew was having a moment as Drake was also on the rise, and “YOLO” was the motto. Skinny jeans in every color and animal print were genderless and pinned to hips with studded belts.

Neon shutter shades were worn under wide-brimmed hats that read something like “I ♥ My Haters” or something equally unhinged. The air smelled like Pink Sugar perfume or Axe–and ‘fit pics were uploaded to Tumblr daily, that is, until Instagram launched in October 2010 and locked us all in a Valencia-filtered chokehold. This was also the last era of intentional mall shopping, when entire looks came together at Charlotte Russe, Journeys, or Forever 21, no link exchange required.

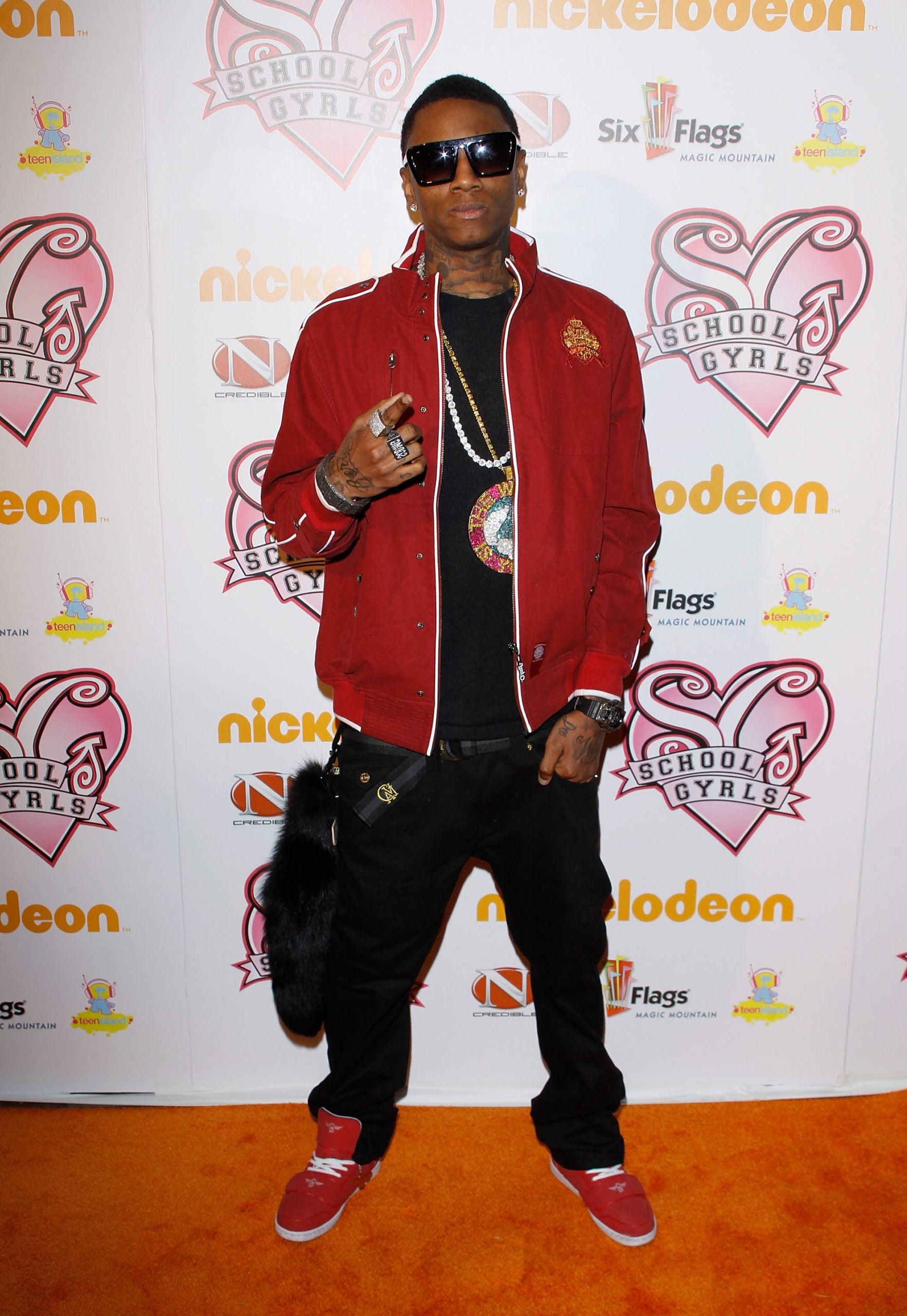

In those days, there was no such thing as “quiet luxury.” Kids got dressed to be seen IRL and online as youth culture began adopting new technologies, and shaping new forms of media. Soulja Boy might blow a lot of smoke on the internet, but he is the very first rapper to go viral.

Platforms like YouTube were moving the dial-up generation into new territory and sharing music and fashion trends at faster speeds. As Soulja Boy and other artists were teaching dance routines on the then-unpolished streaming site, teens across the country were copying not just steps, but styling choices. Slightly reminiscent of the 1980s and the days of “Yo! MTV Raps,” youth-led media, was beginning to dictate style in real time. Not from glossy magazines or TV networks, but from bedrooms, webcams, and early iterations of social media networks.

From high school hallways to HBCU campuses and community college quads, “Swag Era” styling wasn’t confined to one corner of youth culture. It moved across age brackets by trickling upward, a reversal of the usual top-down, celebrity-driven trends. Teens sparked the aesthetic, part skater, part punk, part hip hop star, which college kids soon remixed by layering streetwear with campus-specific staples.

Even postgrads, navigating early adulthood in a shifting economic landscape, leaned into the aesthetic, dressing with a kind of defiant playfulness that pushed back against the pressure to look older. Just as “Yo! MTV Raps” and the rise of streetwear in the 1980s were deeply entangled with the politics left behind by Reaganomics and rising youth disenfranchisement. The “Swag Era” emerged in the wake of a different, but equally sobering reality. The hope-and-change promises of the Obama administration were beginning to dim. The recession had gutted job prospects for college graduates and cast a long shadow over the future.

For many young people, especially Black and brown youth, the loud, clashing outfits, two-toned hair, and “Jersey Shore” style accessorizing weren’t just about attracting attention. They were a refusal to shrink in the face of economic uncertainty, a creative response to stalled progress, and a declaration of presence and pettiness in a world that felt increasingly out of reach.

For many postgrads in the early 2010s, life after college didn’t unfold the way they’d been promised. With student loan debt ballooning, job prospects scarce, and the gig economy just beginning to take shape, a new generation of early twenty-somethings found themselves staring down the barrel of a single choice: struggle, or move back home. The term “failure to launch” became shorthand for stalled adulthood, with tens of thousands of young adults boomeranging back to their childhood bedrooms and piecing together multiple part-time gigs to survive.

But this had little to do with laziness or lack of ambition; it was about structural instability. These were the kids who had done everything by the book: they’d earned the degree while trying to dress the part. Many of them had swallowed the myth of meritocracy whole. And still, they ended up locked out of the very stability they’d been promised.

In that landscape, the expressive freedom of “Swag Era” styling became a kind of refusal. Why dress for a future that has already failed them? Instead, many leaned into a loud, cartoonish, deliberately childish aesthetic. Sesame Street and other character-inspired backpacks, Hello Kitty headphones, marijuana leaf printed high socks, and neon-colored accessories pulled straight from Party City shelves. It was more than a trend; it was satire in motion. A cheeky, exaggerated rejection of the adult world’s seriousness, its grind, its failure to deliver.

If growing up only led to debt and disappointment, why not stay suspended in a version of youth that felt more honest, more expressive, and frankly, more fun? After all, it’s hard to Cat Daddy in business casual! For clubbing, the privileged few who lived throughout this era would activate high and low styling, pairing Christian Louboutin heels alongside Forever 21 bandage dresses. Sky-high Jeffrey Campbell platform shoes or outlandish Giuseppe Zanotti heels and flimsy, multi-patterned Charlotte Russe dresses also hung in the closets of many millennials. Even amid bleak economic conditions, clubgoers of the era made it clear that the party didn’t stop just because the system was broken.

Of course, millennials weren’t the first generation to dress against the grain. Aesthetic rebellion has long served as both a mirror and a megaphone for marginalized youth. In an email, social impact strategist and fashion aficionado Virginia Cumberbatch shared that our resistance has always been stylized: “Our style is inherently political, serving as [a] universal language, consciously and unconsciously communicating our values and beliefs.”

She went on to express that fashion, even at the most “superficial level,” is a “democratization tool.” Cumberbatch added that it has always had the potential to serve as a practice of disruption. “There is a remarkable link between some of the most significant Black and brown social justice movements, cultural shifts, and empowerment campaigns, and the aesthetic choices that were adopted,” she noted.

For instance, in the 1960s and 1970s, the Black Panther Party transformed the image of militancy with leather jackets, berets, and Afros, clothing that signaled Black pride, discipline, and radical resistance. In the barrios of the American Southwest, chola girls perfected their look with dark lip liner, oversized flannels, and nameplate earrings, styling themselves with fierce precision that both declared loyalty and warded off erasure. Often parodied in modern culture, the original aesthetic wasn’t just fly, it was confrontational, coded, and defiantly self-made.

“Swag Era” styling followed in that tradition, not merely a matter of taste, but a response to being forgotten and left behind. Like their predecessors, the era’s neon colors, wild graphics, and attention-grabbing silhouettes pushed back against that invisibility, insisting that joy, play, and self-expression were forms of survival, too.

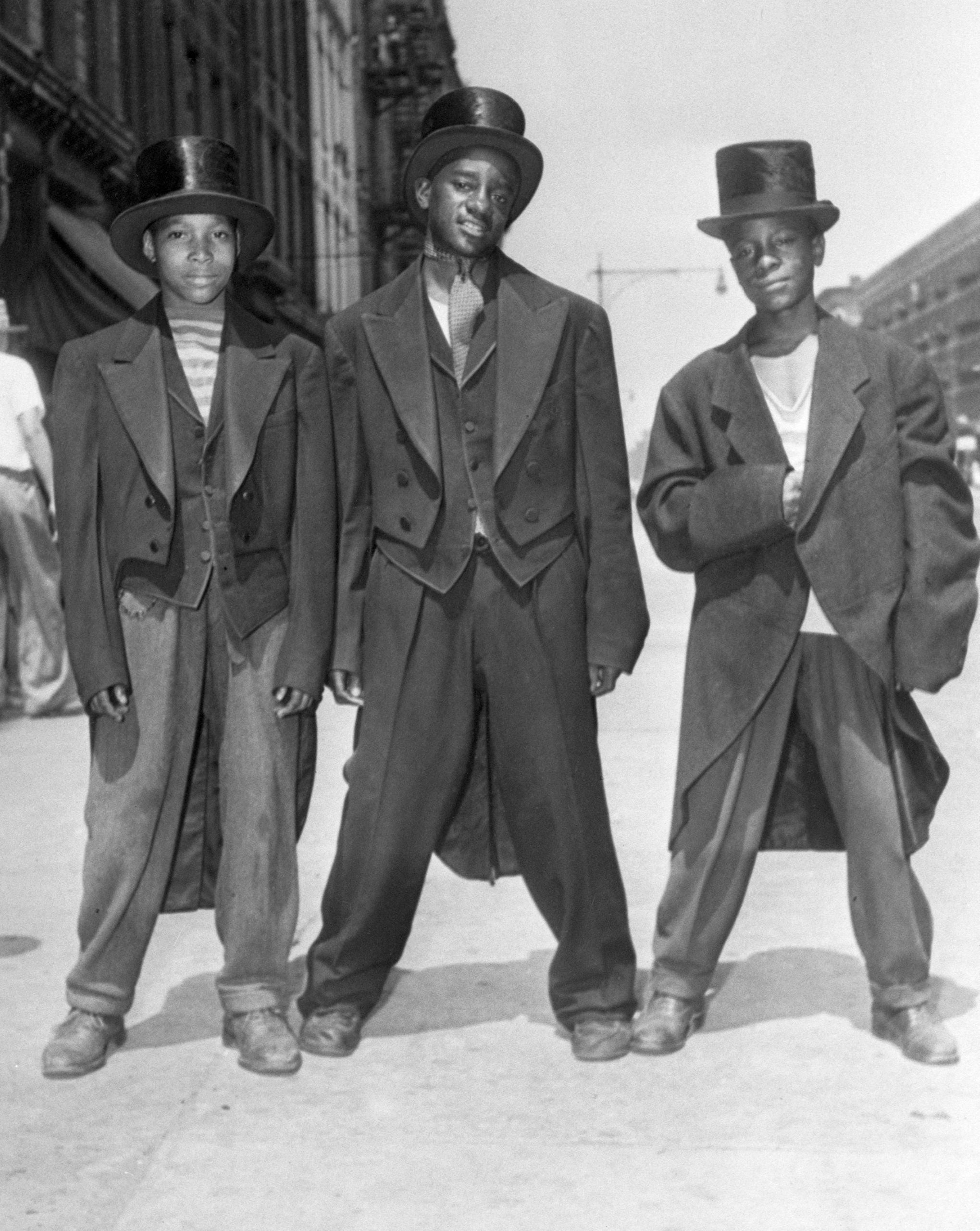

In the 1930s and 1940s, zoot suits were the sartorial rebellion that took over urban city centers like Los Angeles, Harlem, Detroit, and Chicago. To white middle-class America, zoot suits were seen as excessive and unpatriotic, especially during WWII when fabric was being rationed. But to the predominantly Black, Mexican American, and Filipino youth wearing them, zoot suits were a declaration of cultural identity, a refusal to conform to white, working-class respectability politics, and a claim to visibility, fun, and dignity in spaces of racialized exclusion. The zoot suit was the swagger of the moment and became a symbol of noncompliance and aesthetic autonomy in the face of racist policing and assimilationist pressure.

Like the zoot suit generation before them, “Swag Era” stylers crafted a visual language that confronted invisibility and refused the lie that respectability guaranteed protection. Even if they weren’t met with the same physical violence, their style and the lives it reflected carried the weight of protest. In this way, the era sits within the broader lineage of cultural expression that helped give rise to movements like Black Lives Matter, where self-definition and public presence became acts of resistance.

The chaotic boldness of the era marked more than a moment in style; it left a lasting cultural imprint. Though fleeting, it was far from forgettable, and not only because the receipts still live online in grainy Facebook albums. These years carved out a visual and cultural space for visibility, for humor, and for hyper-expression in a world that offered few soft landings.

So, is the “Swag Era” making a comeback? Not exactly, or at least not in full. Historical data suggests that fashion trends used to resurface in cycles of about 20 years, which means we’re just now entering a period ripe for revival. But while the word “swag” is reappearing in headlines and hashtags, its spirit hasn’t quite returned.

Justin Bieber’s recent album, ironically titled “Swag,” leans toward barren, beige, and black-and-white aesthetics or the minimal, moody, and stripped of the accessories and attitude that once defined the era. It’s a curious nod if anything, more ghost than homage. And so maybe the world isn’t done with quiet luxury and soft palettes. Even so, the memory of the “Swag Era” still lingers like a flickering neon sign outside a long-shuttered club, buzzing with restless energy. A reminder that style can be unruly, unserious, and still speak volumes.