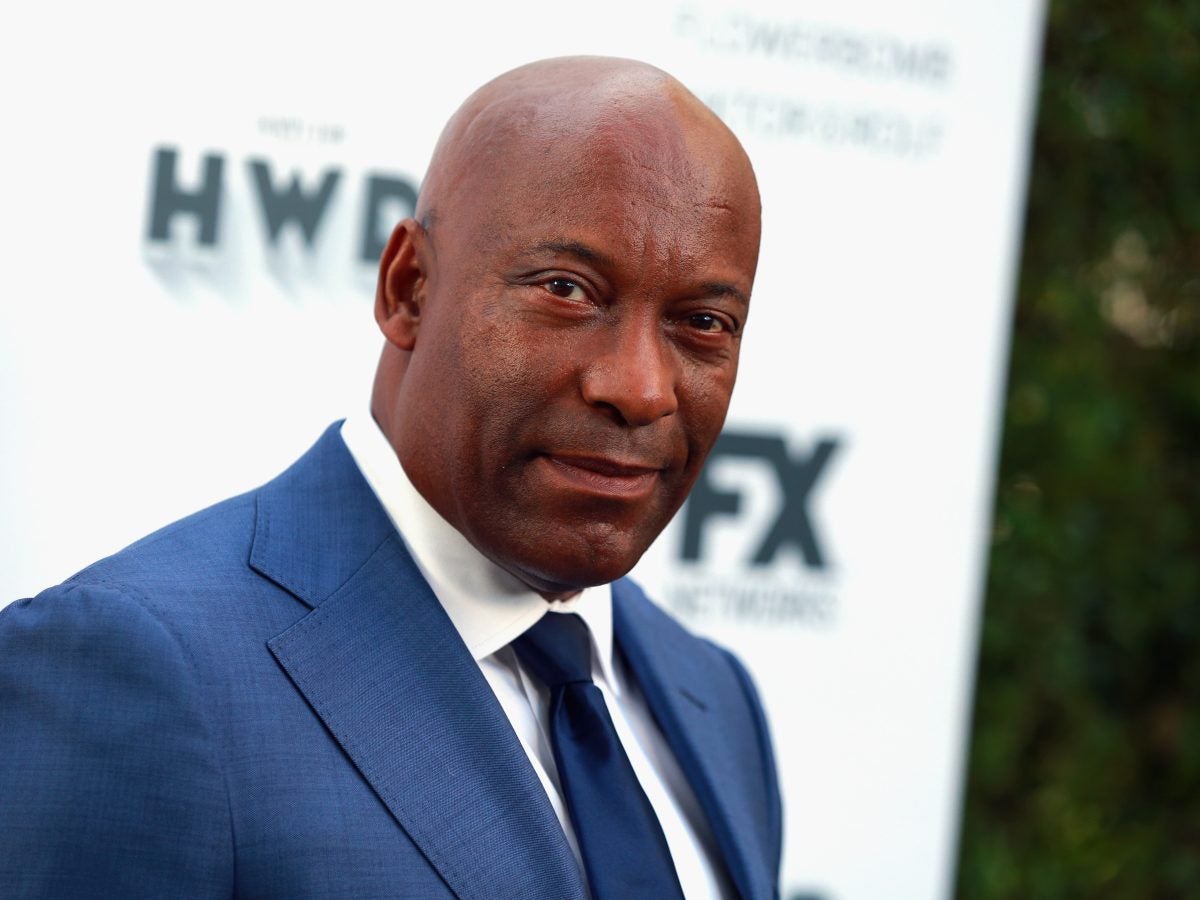

In 1997’s Love Jones, Larenz Tate’s Darius Lovehall tells Nina Mosley (Nia Long) the classic line: “The true goal of an artist is to create the definitive work that cannot be surpassed.” It’s a quote that has stuck with me for years, because it speaks to ambition, and just how rare the feat of perfection really is. For most artists, greatness is something chased across a lifetime, refined through trial, misstep, and time. But every so often, someone arrives fully formed in their craft. John Singleton was one of those people.

At just 24 years old, Singleton accomplished what many spend decades working toward. Think Nas’ Illmatic—but on the big screen. His feature film debut Boyz n the Hood, confronted America head-on, insisting that the lives of young Black people in South Central Los Angeles were not abstractions, but real human stories worthy of empathy. Singleton understood that the urgency of Black life, with all its contradictions and beauty, required authorship from within.

Throughout his career, Singleton advocated that Black people should tell their own stories, on their own terms, without softening narratives to make them more palatable to a wider audience. Violence, tenderness, rage, joy, responsibility, and grief all existed in the same frame, because that’s how life exists. Additionally, what made Singleton extraordinary was not that he was the youngest (and still is) and first African-American nominee for Best Director at the Academy Awards, but it was his vision. He continuously casted actors before the world knew their names, bridged hip-hop and cinema, and returned again and again to the stories this country preferred to ignore. His influence endures because he told the truth early, loudly, and without compromise.

While there are countless reasons to admire John’s work, a handful of projects stand apart for me. The aforementioned Boyz n the Hood was impossible to look away from. Singleton’s insistence on showing Black men as emotionally complex in films like Poetic Justice and Baby Boy, expanded the visual language of Black masculinity on screen. And with Snowfall, the auteur closed his career the same way he opened it; by interrogating systems of power and exposing the consequences they leave behind. Taken together, these works underscore what made him one of a kind.

Boyz n the Hood (1991)

“Breathtaking” still feels like the only word to describe this film. Set in South Central Los Angeles from the mid-’80s into the early ’90s, Boyz n the Hood felt immediately familiar to Black audiences, no matter where you were from. The geography was specific, but the truth was universal. The film follows Tre Styles (Cuba Gooding Jr.), sent to live with his father Furious Styles (Laurence Fishburne), where he reconnects with childhood friends while navigating a neighborhood shaped by violence. It’s a coming-of-age story that never pretends growing up is safe. For audiences outside the community, the film was often a first unfiltered look at urban America. For those within it, it was recognition. The movie understands how quickly things can change, how joy and grief coexist, and how survival itself can become the goal.

The film was a testament to Singleton’s vision, but it introduced people like Ice Cube, Morris Chestnut, and Regina King to cinema, while showcasing the rising power of Nia Long, Angela Bassett, and Fishburne. Written and directed as Singleton’s feature debut, Boyz n the Hood earned him Academy Award nominations for Best Original Screenplay and Best Director, making him the first Black filmmaker—and still the youngest—to be recognized in the category. While films like New Jack City and House Party were also expanding space for hip-hop artists on screen, Boyz n the Hood helped solidify a shift (one that Singleton would continue throughout his career) in bridging hip-hop and cinema with intention. More than 30 years later, the film endures not because it told the truth, unapologetically.

Poetic Justice (1993)

Plenty of love stories existed before Poetic Justice, but when it arrived in 1993, it felt unlike anything that had come before it. Following the intensity of Boyz n the Hood, John Singleton chose to tell a more intimate story centered on young Black love—specifically, the interior lives of young Black women. Starring Janet Jackson in her feature film debut alongside Tupac Shakur, Poetic Justice offered a romance rooted in vulnerability.

The film follows Justice (Jackson), a guarded poet still grieving loss, and Lucky (Shakur), a mail carrier and devoted single father. Singleton humanized both characters, but told a refreshing story regarding the Black male. In Poetic Justice, Black masculinity was allowed to be gentle, patient, and emotionally available, which was an image rarely seen on screen at the time. In juxtaposition to his debut, Singleton wasn’t aiming to deliver a sweeping social thesis. Instead, he wanted to create a space for Black women to exist at the center of a love story without compromise. Over time, the film has taken its place in the canon of Black love stories, and reiterates the fact that love conquers all.

Rosewood (1997)

Racism has always been embedded in American history, but few films confront that reality as directly as Rosewood. Inspired by the true story of the 1923 Rosewood Massacre in Florida, the film revisits a Black town destroyed after a white mob murdered its residents and burned the community to the ground. For decades, the story was buried—absent from classrooms, like several others. (Tulsa, Georgia, you name it.)

Ving Rhames stars as an outsider who arrives in town and helps residents defend themselves, while Don Cheadle plays Sylvester Carrier, a man fighting to protect his family amid escalating violence. Jon Voight appears as a white shop owner caught in the moral tension of the moment. What’s scary is that this story wasn’t that long ago, and Singleton places viewers inside the fear, chaos, and impossible choices faced by the people of this Florida community.

The film struggled commercially, despite strong critical response. Screenwriter Gregory Poirier later noted that audiences weren’t ready to confront such a brutal chapter of American history. Singleton understood that reaction, in an interview with FilmScouts later that year he pushed back against claims of excessive brutality. “People say it’s violent. I don’t think it is, and certainly not as violent as it was being there,” he said. “I wanted to make you feel you were there. But then maybe Americans are afraid of it because of their own racial problems. They’re all f****** up over race, you know.”

Even amidst its lack of commercial success, Rosewood stands as one of Singleton’s best films, and a powerful reminder of this country’s checkered history.

The People v. O. J. Simpson: American Crime Story (2016)

In the months following the 20th anniversary of O.J. Simpson’s murder trial, a wave of projects revisited the case, each attempting to explain why it had consumed the country the way it did. FX’s The People v. O. J. Simpson: American Crime Story gave a dramatic look on how race, power, and media shaped both the trial and its aftermath. With an ensemble cast that included Courtney B. Vance, Sterling K. Brown, Sarah Paulson, Cuba Gooding Jr., John Travolta, and David Schwimmer, the series was one of the best releases that year.

Singleton directed the fifth episode, “The Race Card,” and it remains the shows’ most searing hour, at least for me. The episode shifts the trial’s focus, forcing race into the foreground where it had always existed. The use of the “N-word,” the strain between Johnnie Cochran and Chris Darden, and the courtroom power dynamics all land with perfection.

Vance’s performance as Cochran reaches its peak here, culminating in a blistering courtroom moment that really cut through the screen. The episode earned Vance the Emmy for Outstanding Lead Actor in a Limited Series or Movie and brought Singleton an Emmy nomination for directing. “The Race Card” works because its director understood how race operates in America—and he helmed the episode accordingly.

Snowfall

After the impact of “The Race Card,” John Singleton reunited with FX for Snowfall, a series that allowed him to return to familiar terrain. Set in 1980s South Central Los Angeles, the show follows the rise of Franklin Saint (Damson Idris), a young man pulled into the crack cocaine trade as it reshapes his family, his neighborhood, and his sense of power. It also reveals how global politics and American ambition collide.

In Snowfall, Singleton refuses to isolate the crack epidemic from the systems that put it into play. Alongside Franklin’s ascent, the series tracks CIA operative Teddy McDonald (Carter Hudson), whose covert operations in Nicaragua funnel consequences back into Black communities at home. The series also marked Damson Idris’ arrival, anchoring the show with a performance that grows darker and heavier as the seasons unfold.

Snowfall would be the last project Singleton worked on before his death in 2019. Fittingly, it stands as a culmination of his career-long concerns: power, responsibility, and the cost of systems designed to fail the people living inside them.