It is said that beauty is in the eye of the beholder, but perhaps its true reflection is best illuminated within the essence of our being–radiating outward as a subtlety aesthetics alone struggle to convey but that humanity exudes intrinsically. When met with meditative reflection and intuitive imagination, its spirit comes to life. For quilt artist Bisa Butler, honoring the heritage of Black creativity and elucidating what is felt more than it is seen is how she fabulates portraits that quilt beauty into being.

Her development as an aesthete began with her mother, first in nature and then in fashion. “Beauty to me, early on, was what you were seeing but also what you were feeling. That sensation, the softness of relaxation, feeling the breeze on your face, the sun on your skin, were my early impressions of beauty,” Butler tells ESSENCE as she recalls time spent with her mother outside, cultivating presence and serenity within herself. She taught her that self-empowerment and self-knowing allow you to express yourself more freely.

“Later that transitioned to fashion and beauty. I loved dolls and I really wanted my dolls to be fashionable because I was always seeing my mother and my aunts who were really stylish,” she shares. “I would say I was around 10 or 11 when I started really noticing clothing and texture and fabrics.” Her mother taught her how to sew to make clothing for her dolls, unknowingly planting the seed for her innovation in quilt-making that would define her career. In a sense, starting internally and drawing inspiration from the external world around her, her mother instantiated an understanding of beauty that captured the core of an individual.

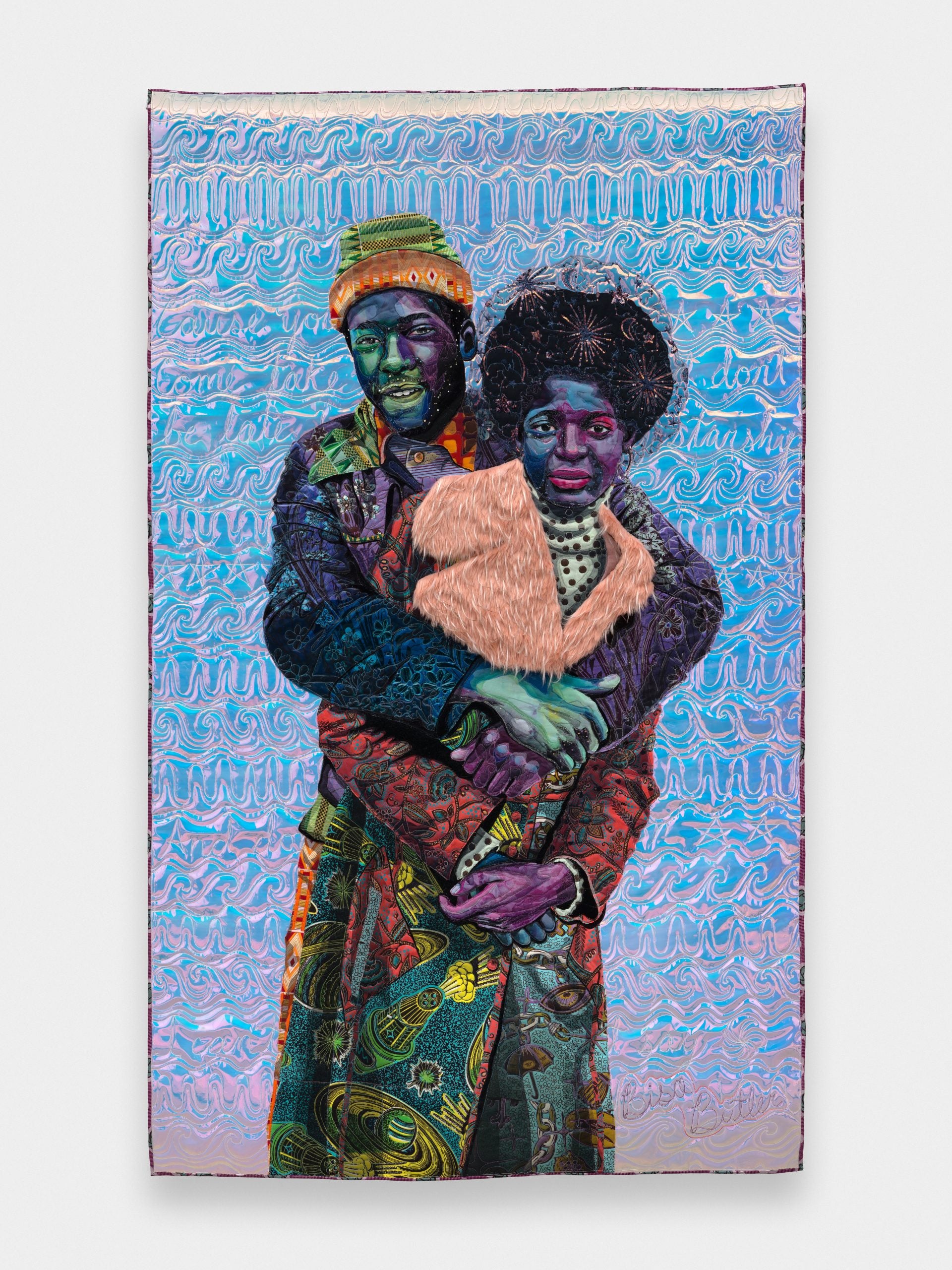

“I think that my quilts are like the embodiment of a real Black person and not the stereotype.” she shares. Larger than life and rich in technicolor hues, Butler’s quilt paintings, evocative of renaissance-style portraiture, engender visceral exchanges between the past and the present, subject and viewer, perception and persona. “It’s something that’s really important to me, to get below the surface,” she shares. They are equal parts figurative elegy and invitation for intimate dialogue between souls who would otherwise never have met as her works close the distance between decades and the diaspora.

A child of the ‘70s and student of the indelible AfriCOBRA generation, Butler is considered a daughter of the Black Arts and Black Is Beautiful Movements of the 1960s. “To always have my art aligned with activism and Black liberation is something that is very important to me. It was a task and mantle that was passed down to me when I was at Howard, and it resounds and lives on in me to this day that I have a responsibility to help my people,” she says. She studied under Jeff Donaldson, AfriCOBRA co-founder, at Howard University, where her artist training carried on the legacy of revolutionaries. First focusing on painting and later transitioning to her signature quilts, her studies were defined by an investment in the reclamation of Black aesthetics. Its effects are evident in her metamorphic depictions of her subjects.

“The founders of the Black Arts movement were specific about that, that yes, the roots of their artwork could trace back to Africa and Europe, but they were creating something new and it was going to be a Black American aesthetic.” With her Louisianan mother and Ghanaian father, she is uniquely positioned to speak to these connections across cultures. As much as she draws on the ‘Kool-Aid Colors’ coined by her AfriCOBRA predecessors, she also incorporates African textiles like Kente cloth to deepen the meaning of her work in relation to gender, geography, and time.

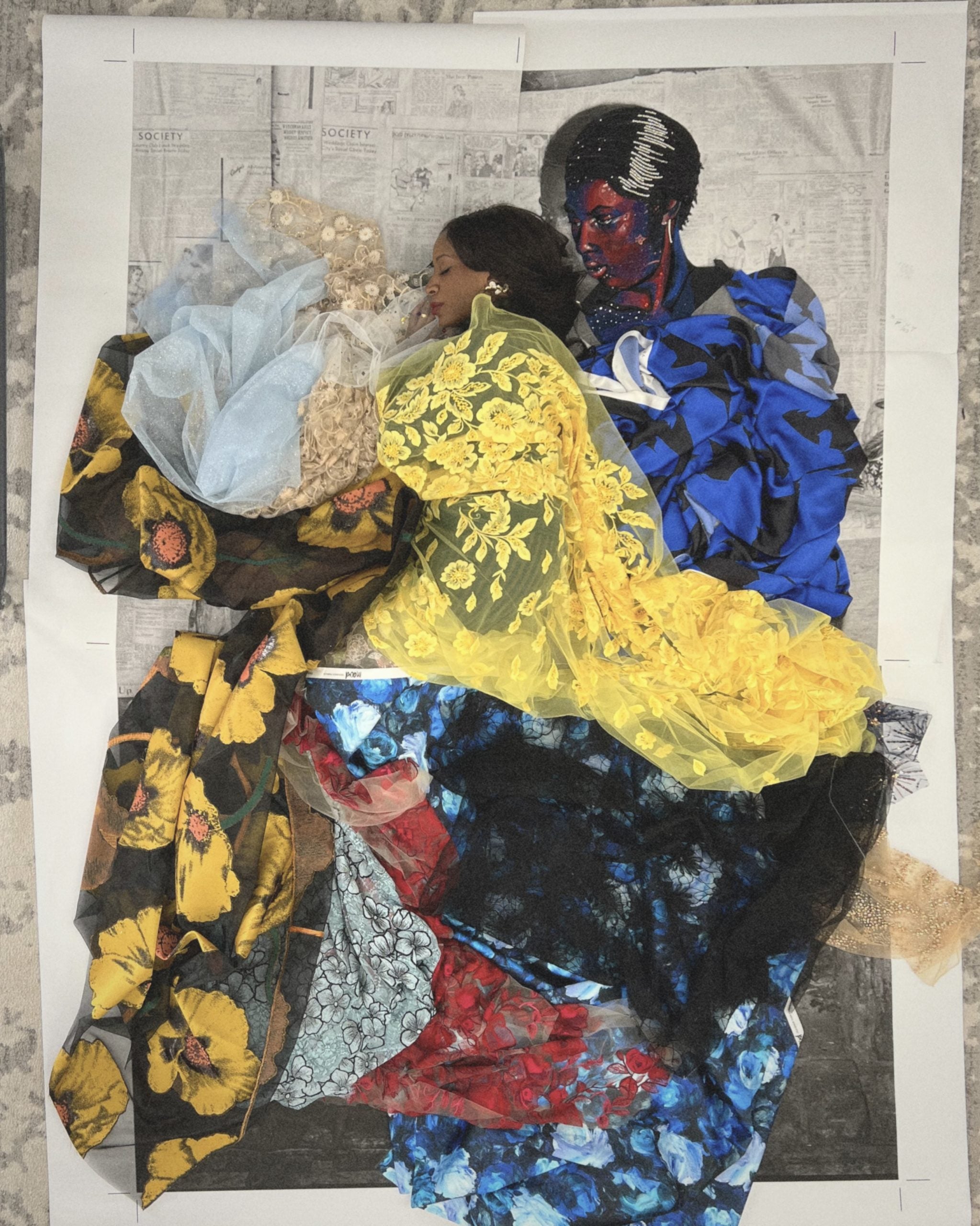

She draws from archival photography, when not working with more recognizable imagery like the work of Gordon Parks, and fabrics rich in cultural history to reimagine individuals whose identities have often been collapsed by records. “One of the things that struck me when I came across the archives is just how many of our images were just labels and had no other information whatsoever,” she reveals. With reductive names like Negro in Greenville or Negro Boys on Easter Morning, for many of her subjects, these titles become the entirety of their visual remembrance within public record. But through her quilting, fibers serve as medium both materially and spiritually in the formation of ebullient expositions of Black life.

Upon meeting the gaze of her sitters, their souls speak through chiffon silks and chantilly lace where shutter speed sewed silence. As photography captures a singular moment, often flattening identity within the constraints of static exposure, her quilts extrapolate beyond representation to animate the depth of their humanity. Each layer of fabric illuminates idiosyncrasies unique to their being–luminous skin, captivating curls, striking eyes that pierce through projection with profound conviction.

These nuances are considered with a close looking and deep meditation that initiates her work. “I usually blow up a photo a little larger than lifesize, so I’m looking at this person’s face very carefully in high detail…” Enlarging her source imagery to this scale, she welcomes the disposition of her subjects into the room and not just their physical distinctions. “I try to pick up all the nuances of…how they’re holding their hands, their body language. Like what is their body language saying?” She gives life to what they held within that a photograph might not reveal.

A signature part of this is unearthing the luminosity. Her revelatory aesthetic practice fuses blackness, both visually and culturally, with vibrance and light. Viewing her works in person, their radiance is mesmerizing as the fluorescent fabrics emanate the essence of a person unbeholden to literalism. They quite literally glow, employing similar evocations of Black Light as her quiltwork forebear Faith Ringgold, where Black, rather than white, is the basis from which light is generated.

In doing so, she is in conversation with a lineage of artists enacting visual interventions in the representation of skin tones. “When I was in school, my professors really encouraged us to explore the depths of our actual melanins. Like, how do you make brown without squeezing brown out of a tube?” she shares. Instead of brown fabric, she employs striking fuchsias, electric greens, vital reds, and enchanting blues to emulate the richness in complexion without the associative connotations of skin tone. It functions as another layer in the storytelling of her subjects bringing to light the intensity of emotion and identity that can be expressed through color.

“I’m taking all this time to breathe life into this portrait,” she says. “And I think that what happens is the pieces do tend to take on a spirit of their own and that the only reason I know this is because people respond to it in that way.” In quilting she fashions a new way of seeing, one that is grounded in connection between her subject, her viewer and herself as an artist. “The beauty is what you’re seeing but also what I’m feeling as the artist or what I imagine the person is feeling.”