I hate feeling nauseous. That skunking, hot-cheeked anticipation of your body turning on you. I felt the nausea curling in my stomach as I sat cross-legged on a slim padded mat beneath the ceremony tent, surrounded by soft shadows and the low thrum of a drum somewhere behind me. The Jamaican mountain air clung close, warm and perfumed with sage. Though I’d microdosed psilocybin a few times in the past, this was new. A full ceremonial dose.

Facilitators moved quietly through the space, checking in with those ready for a booster. When one knelt beside me, I wavered before accepting the second cup of tea. I sipped quickly, not from reverence, but from resolve. I didn’t feel well, and I wanted to get it over with before I second-guessed myself.

The same facilitator guided me to the bathroom when my nausea swelled. The mirror had been covered with a cloth, a gentle precaution in case our reflections turned out to be too startling. Better not to see ourselves mid-unraveling. So, I stood in the quiet, holding on to my breath and to the moment. Nothing came up. No purge.

Then, halfway back to the tent came the sobs. Heavy, heaving bottomless sobs. I barely registered the transition. It was as if something ancient had clawed its way out of me. I crumbled onto the patio sofa beside the tent, the facilitator never far from reach. My face twisted, my throat scraped, tears and snot ran freely. On my family’s ancestral land, I unraveled.

I had come to Good Hope Estate in Trelawny, Jamaica, for Beckley Retreats’ second Sanctuary Retreat for Women of Color. Lush, expansive, and now a dedicated space for wellness retreats and weddings, the estate once operated as a plantation, a dissonant truth we all had to hold. That the estate is still white-owned only deepened that tension. Some women spoke of it openly. I felt it too: the weight, the ghosts, the complicated privilege of returning here for healing.

When Beckley Retreat first invited me to attend and reflect, I hesitated. I’d taken psilocybin a handful of times in microbuses, always in the form of a chocolate bar, but never in ceremony. The idea felt both deeply unfamiliar and somehow overdue. Still, what ultimately drew me was the care. The design of the retreat was specific, considered. Each participant underwent a thorough preparation and intake process: screening for mental health conditions, medications, and trauma history, as well as virtual individual and group therapy sessions.

What also made this retreat truly unique was its cultural intentionality. The team (primarily Black women, along with two men of color) created a container that felt reverent, grounded, and culturally safe. Co-leads Dingle Spence, M.D., a Jamaican palliative care physician, and Hanifa Nayo Washington, a healing justice practitioner and sacred ritualist, were joined by Beckley COO Vian Morales and facilitators Elizabeth Goffe, Mandi Bent, Marion Johnson, Micah Tafari, and Eber Rodriguez. We weren’t being observed or explained to. We were being held.

Scientific studies suggest that psilocybin, the psychoactive compound in magic mushrooms, can stimulate neuroplasticity and interrupt entrenched patterns in the brain. From depression and anxiety to PTSD and even cluster headaches, research has shown promise across them all. But what I experienced wasn’t a fact or finding. It was a slow unraveling of tension I hadn’t known I carried.

I arrived late, after a long travel day that ended in a shared van ride from the airport. A Black woman who’d been sitting across the aisle from me on the flight turned out to be one of the attendees. We began discussing work, loss, and the purpose of our gathering. Transition emerged as a recurring theme among our predominantly Black group. Nearly every woman I met at the retreat was in the middle of some threshold. Some had just ended relationships or started new careers. Some were mothers questioning their roles or recalling traumatic births. Some were coming home to themselves.

Each morning began with various movements and meditations under a high-beamed, open-air pavilion. At breakfast, the chefs, who reminded me of my aunties and grandmothers, greeted us with warm calls of “Good mawnin’!” They laid out plates, like sailfish, roasted breadfruit, callaloo, and sweet, ripe golden mango. The food was grounding, the care unmistakable. And yet, that dissonance stirred again: this was ancestral land, yes, but whose ancestors had labored here, and whose still held the deed?

Before the first journey, we were reminded that the ceremony itself was the inhale; the integration, the exhale. We were asked to honor “noble silence” and not speak with one another and trust the medicine and space. I tried. I laid back, eyes closed, listening to others weep or hum or whisper. For hours, I felt little more than mild disorientation. But toward the end, I began to spiral emotionally and physically into confusion. At one point, a woman growled, low, sharp, and unrelenting. The sound, animalistic and jarring, startled me. I wasn’t prepared for how destabilizing it would feel to witness someone else’s release in such a raw form. It made me realize just how vulnerable we all truly are once the medicine takes hold. I didn’t know how to navigate the intensity. So I broke “noble silence” and reached out to others nearby. “When is this over?” I wondered aloud. Later, an attendee confided that she, too, had felt the energy shift into something untethered. We hadn’t known what to do.

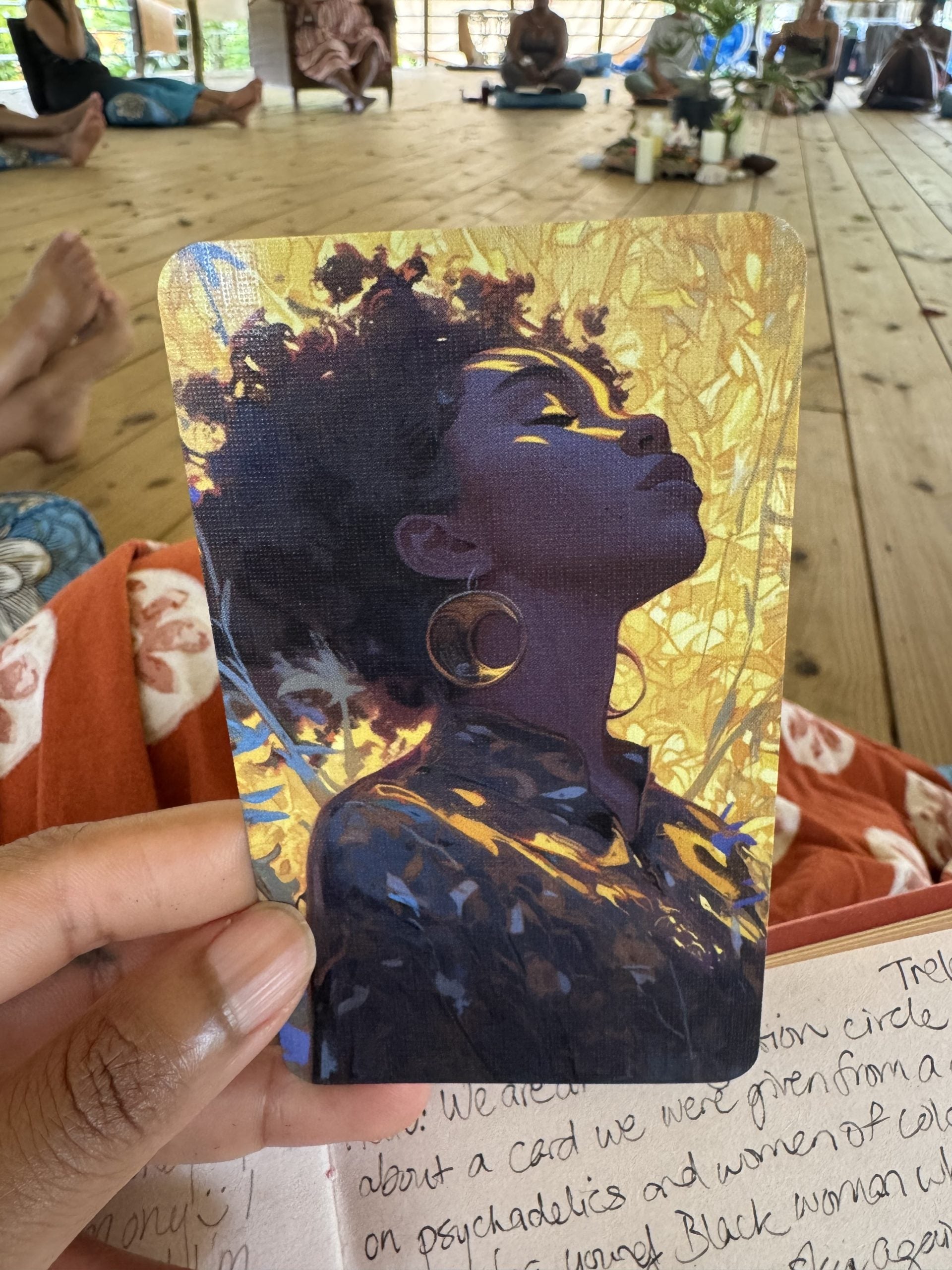

The next day, Spence passed around Lucille Clifton’s pivotal poem “won’t you celebrate with me” in our integration circle. As we took turns reading the lines aloud, the gravity of what we were doing, celebrating how “everyday something has tried to kill me and has failed,” settled in. Still, I struggled to lower my walls. Something remained locked. The second ceremony would change that.

I had set clear intentions this time: surrender, soften, trust. I wanted to let go of the internal pressure to always be good, to do right, to carry everything. I fought the medicine at first. Fear, anxiety, and resistance were all present. But then something gave. Amid the sobbing, I spoke about love, family, overwhelm, the ache of always trying, doing, proving. The facilitator stayed with me, tissue in hand, grounded. She didn’t try to fix it. She simply let me speak, let me cry. How would I remember this? How could I possibly write about this? “I’ll remember for you. Just tend to your spiritual garden,” she said. “Baby steps.”

By the final evening of the retreat, the energy among us had shifted. We dressed in flowing fabrics and gathered under the stars for dinner at a long, elaborately set table. Laughter came easily. So did tears. Later, we walked to a bonfire, where we each hurled a stick bearing something we were ready to release into the flames. “Irie!” we finally yelled into the dark, crimson flowers soaring from our hands into the inky night sky. The fire cracked and hissed alongside soft drum beats. We weren’t fixed. We weren’t cured. But we were softened.

In the weeks that followed, our WhatsApp group filled with gentle check-ins, smiling selfies, updates about tiny breakthroughs, and quiet mornings. We would gather again on Zoom for integration gatherings, sharing how the ceremony had rippled through our lives.

This retreat didn’t erase my mental block. But with the care of Beckley’s team, psilocybin-assisted therapy helped me meet it with reverence. It gave me space to listen to myself without judgment. To fall apart without fear. This is what it can look like for Black women to be held in our fullness, emotionally, spiritually, and psychically. To gather not in service to others, but in devotion to ourselves. To come home.

And now that I’ve had that taste—sweet, sacred, and unshakeable—I want it for every Black woman I know.