In a quiet neighborhood of Adenta stands a bright yellow house behind a tall black gate. Before entering, visitors are invited to pause and read The Tenderness Manifesto by Mbella Sonne Dipoko. It feels like a threshold ritual—an opening of heart and mind before stepping into the inner sanctum. Once inside, the space unfolds: shelves upon shelves of books by Black writers from across Africa and the diaspora, a high, open ceiling that lets light filter in, walls lined with framed portraits of thinkers and storytellers.

This is the Library of Africa and the African Diaspora. A place where literature becomes both archive and altar, where the past, present, and future converge in quiet communion.

For the library’s founder, Sylvia Arthur, the project began long before the library’s doors first opened in 2017. Born and raised in the United Kingdom to Ghanaian parents, she grew up surrounded by books but estranged from the literature of her ancestral home. “I was really trying to learn more about my African culture through literature,” she recalls. During a stint living in Brussels between 2010 and 2012, that search became almost obsessive. “I became a scavenger,” she says. “Every Saturday morning I was in the bookshops, searching for books by Black writers generally and African writers in particular.”

What began as a personal quest became a collection — 1,300 books gathered from secondhand shops, publishers, and obscure catalogs. But the collection soon outgrew her Brussels apartment, spilling into a London flat and eventually across continents. “When it became too much for even there, I would ship them to my mum’s house in Kumasi,” Arthur remembers. “I had a room there that was my own little library.” That room would become the seed of something much larger.

The idea crystallized on one of her early trips back to Ghana. A lifelong habit of exploring bookstores in new places had led her to Ghana’s literary landscape, but she found little that spoke to her. “The bookstores were very vanilla,” she says with a wry smile. “They had no direction. It was all commercial fiction — Danielle Steel, Dan Brown — or business and religious books. None of it was relevant to the culture or the people of Ghana.” Even the works of Ghana’s own literary giants — Ayi Kwei Armah, Ama Ata Aidoo — were nowhere to be found.

Arthur’s frustration became fuel. If the books that told Africa’s stories weren’t accessible on the continent, she would make them so. “I wanted to give people access to those books,” she says. “Which sounds strange — giving them access to their own culture, their own literary heritage. But that’s what it was.”

Still, Arthur knew from the beginning that she wanted LOATAD to be more than a place that housed books. With a background in journalism and writing, she envisioned the library as a space that would activate literature — not just archive it. “We’ve had music performances, film screenings, discussions, debates,” she says. “One of the biggest obstacles I faced at the start was people saying, ‘Why should I come to a library? I’m not a student.’ They didn’t realize that reading is a lifelong endeavor, a pleasure — not just an academic thing.”

That sense of activation extended to the creation of a writers’ residency, a rarity on the continent. Arthur, who had attended residencies like Hedgebrook in Washington and Santa Fe Art Institute in New Mexico, understood their transformative power. “They were such enriching and liberating experiences for me,” she says. “I wanted to be able to do that on the African continent.” Today, LOATAD hosts writers from across Africa and the diaspora, offering them time, space, and a deeply rooted context in which to create.

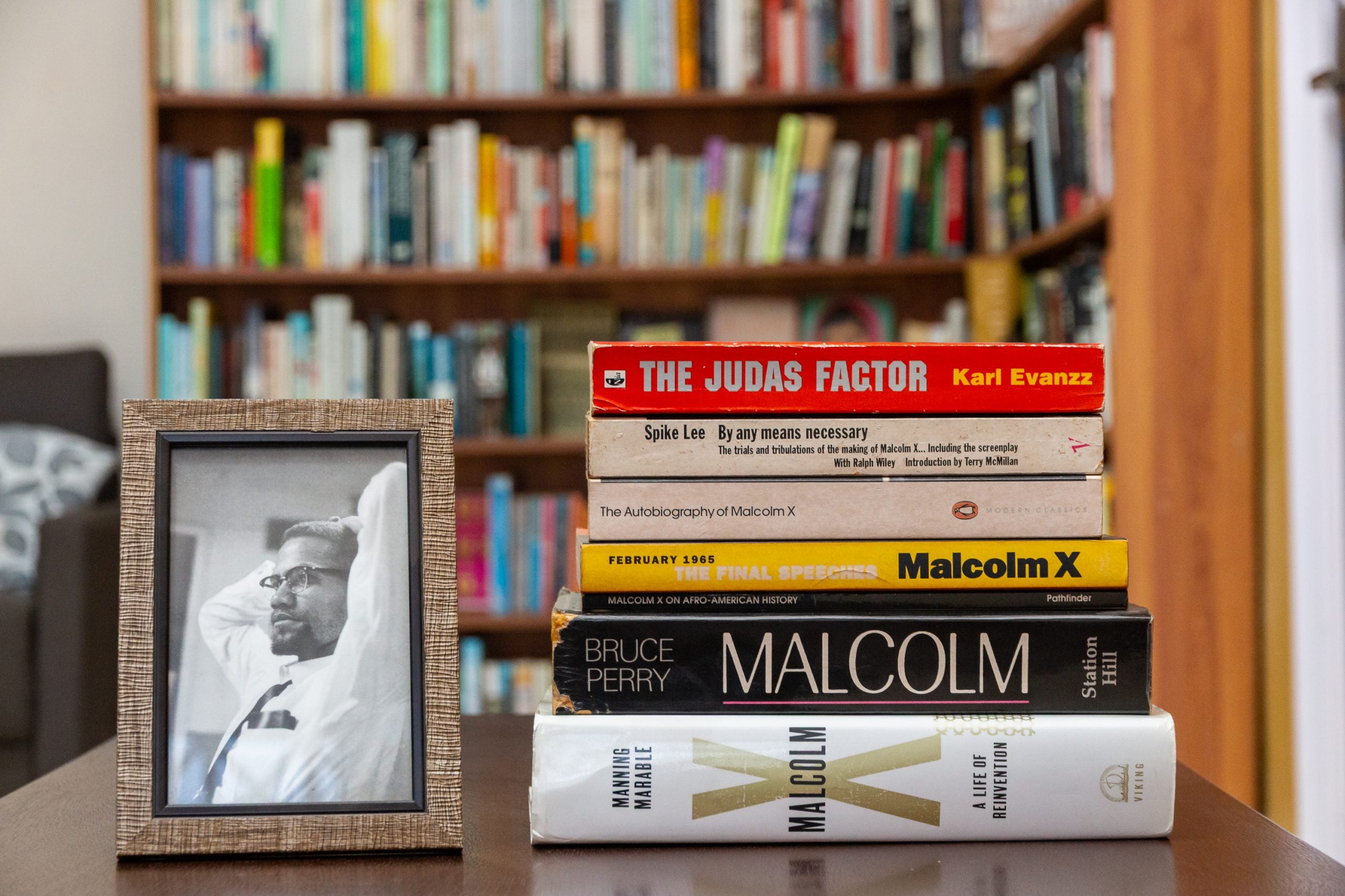

The library’s earliest shelves reflected Arthur’s own reading life. “It was guided by my taste,” she admits. “In the beginning, it was very non-fiction focused, because that’s where my interests lie.” Poetry was almost absent — until patrons began asking for it. Ghana, as Arthur discovered, is a country where literature often takes the form of poetry and drama. “People would come in and ask, ‘Do you have this collection? Do you have that?’ And I didn’t. So I would go and get it.” The library’s now-rich poetry collection, she notes, grew from those conversations.

Children’s books were another gap. “I don’t have children, so I had no need for them,” Arthur says. But repeated requests from visitors pushed her to build a substantial children’s literature section, now housed in two satellite libraries — one at Gemstar School in Ashaiman and another in a rural community outside Kumasi. These outreach efforts illuminate LOATAD’s dual purpose: to serve as a hub for intellectual life and as a tool for literacy and empowerment in local communities.

Arthur is clear that curation is not a neutral act. “I think the collection is very political,” she says. “It has a specific identity and is one that’s reflective of who I am, but also of a Pan-African, internationalist, intersectional Blackness and Africanness.” Even the library’s “World Books” section — the only area not dedicated primarily to writers of African descent — resists Eurocentric literary canons. “It’s not Shakespeare and the so-called classics,” Arthur notes. “It’s the rest of the world — voices and stories that exist outside of Europe and America.”

This intentionality shapes how the library serves its dual audience: the local Ghanaian public and the global diaspora. For Ghanaians, LOATAD offers access to a literary heritage that has long been sidelined. “It gives local people not just knowledge of the outside world, but a connection to themselves,” Arthur says. She recalls a tour with two young Ghanaian men at LOATAD’s second location. A week later, one of them called her. “He said, ‘I’ve been thinking about the door with the Toni Morrison picture above it. I think you should call it the Door of Return, because I feel like I’ve returned to knowledge of myself by being in this library.’”

The name is a deliberate inversion of the “Door of No Return,” the infamous passage through which millions of Africans were forced onto ships bound for enslavement in the Americas. “When you pass through our doors,” Arthur says, “you are literally coming back to knowledge of yourself that has been suppressed, erased, and vilified.”

For members of the diaspora, the journey is equally profound. Though access to books is easier in places like London or New York, the narratives available are often shaped by colonial and Eurocentric frameworks. “Even in the diaspora, you’re told your people are illiterate, that they have no written history,” Arthur says. “You don’t see yourself represented.” In this context, LOATAD becomes a site of reconnection not just to Africa, but to the full breadth of the Black literary tradition. “It’s easy to feel disconnected from Africa, and even from each other,” she reflects. “But when you walk into our space, those connections become real.”

The library’s walls themselves reinforce that truth. Portraits of writers — from Chinua Achebe to Morrison — remind visitors of a shared lineage that transcends borders. “People tell me it really hits them,” Arthur says. “That we are a global people. And we are all connected.”

That sense of connection continues beyond the library’s doors. Over the years, LOATAD has found supporters and kindred spirits across oceans: an African American man in Chicago who shipped boxes of books; a professor in London who donated his life’s collection; a group of archivists from the UK who traveled to Ghana to help organize LOATAD’s archives, free of charge. Others contribute through small but steady gestures — a monthly donation, a shared post, a book left behind for someone else to discover.

Beyond its shelves, the Library of Africa and the African Diaspora serves as a cultural home for Black writers and readers from around the world. It offers writing residencies that allow artists to live and create within its walls, surrounded by the works of those who came before them. Residents draw from the energy of the space, the hum of Adenta outside, and the rhythm of Accra beyond. The library also hosts readings, film screenings, and community gatherings that invite people to think, feel, and imagine together.

Arthur says that, while libraries are not businesses, they thrive on relationships and the generosity of people who see themselves in the work. “We’ve always been open to all the ways people want to show up,” she says. “Sometimes it’s money. Sometimes it’s books. Sometimes it’s their time, or their ideas, or just their belief in what we’re building here.”

Today, LOATAD continues to evolve and expand its programming, growing its collections, and deepening its impact. But at its heart, it remains what Arthur always envisioned: a space that transforms books into bridges. Where the act of reading is both deeply personal and profoundly political. And as Arthur reflects on what it means to have built something like this — a home for Black stories, carved from love, persistence, and imagination — she smiles.

“People come here and tell me it feels like home,” she says. “And that’s really it. That’s what I wanted. For us to know that home can be found — and built — in our own words.”