“Can I ask what kind of name is ‘Okla?’” Bun B wondered aloud before our conversation began. “I’ve never heard that before.”

Obviously, the fact that Bernard “Bun B” Freeman wanted to know the origin of my name was humbling, to say the least. But it also gave me insight into the way that his mind works. As an artist who helped define Southern rap’s golden era—and hip-hop in general—the rapper moves with the curiosity of a man that still has something to prove. It’s probably the reason why he is who he is. With his solo debut album turning 20 this year, and a rap career that spans far longer, he has a whole lot to reflect on.

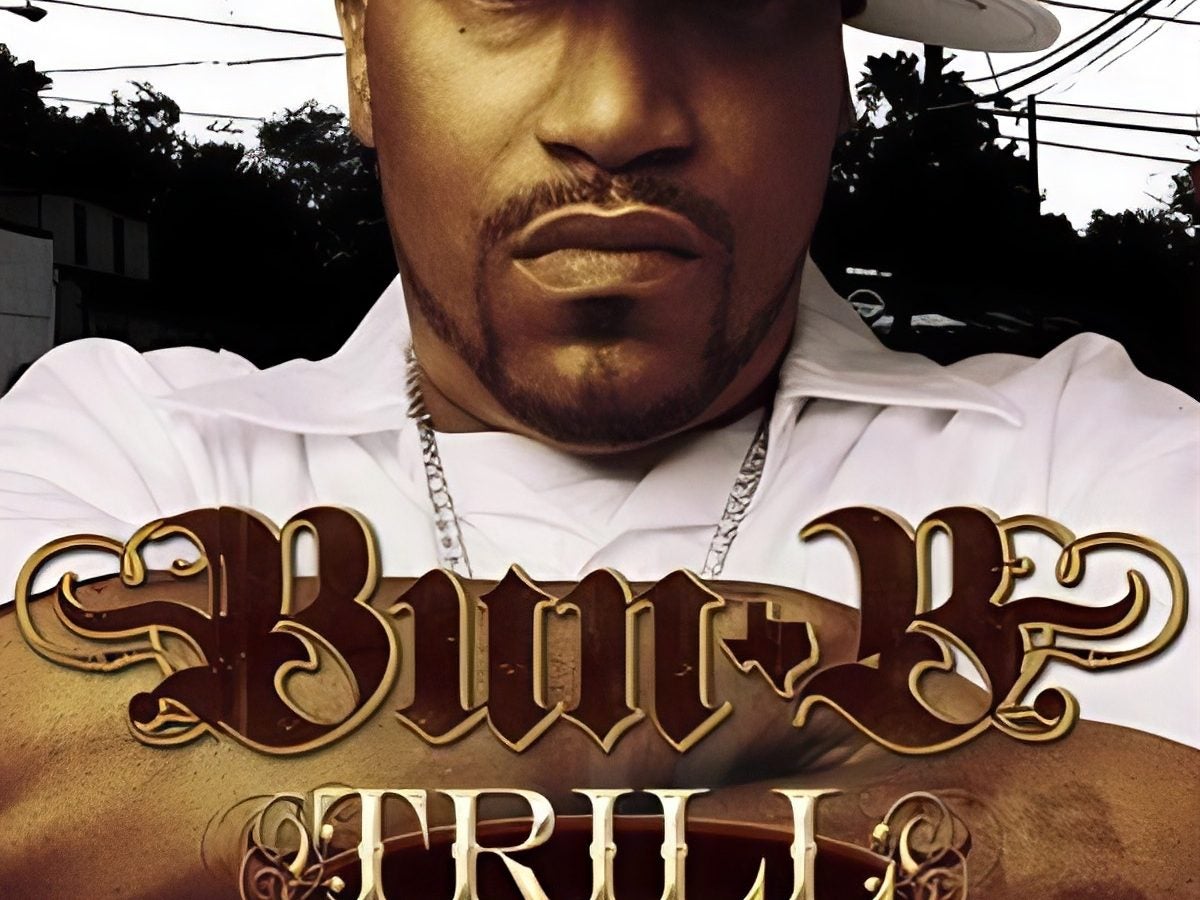

The year is 2005. It had been almost four years since the release of Dirty Money, and stands as perhaps the most uncertain time of Bun’s career. With UGK’s other half—Chad “Pimp C” Butler—facing an eight-year prison sentence, it was imperative that the group remained a strong presence in the music industry. Enter Trill—the 17-track opus that featured many of the who’s who in Hip-Hop. Jay-Z, T.I., Scarface, Juvenile, and production from Mannie Fresh and Jazze Pha—what possibly could go wrong?

“I was very vulnerable during the recording of this album,” Bun said. Trill marked unfamiliar ground for the artist. For the first time, he had to move alone in a sense. Find his own sound, his own footing, and his own way forward. With Trill, every choice carried weight, not just for himself, but for the group that he and Pimp C built together. What emerged was a classic, and proof that UGK’s spirit could still thrive, even in separation.

As we sit down to talk about his debut album, his partnership with Crown Royal, and the city that made him, it’s clear that Bun B’s story isn’t just one of survival. It’s about standing tall in every season—and keeping it trill all the way through.

ESSENCE: Congratulations on Trill turning 20 this year. When you look back at that time, what stands out to you the most about where you were creatively as an artist?

Bun B: I was a bit uncertain of things. You have to understand, Pimp C had just been given an eight year prison sentence. So we didn’t know exactly how long he would have to be incarcerated, how long it would take for him to come back and actually be an active part of UGK, and what was going to become of me because my life had been fully revolving around the group. And what could I do to try to sustain his name, the viability of the group, and the possibility that we can get back to creating music together upon his release. So there were a lot of things that were coming into play for the first time. This is my first attempt at a solo album. I had never produced a body of work solely built around me, and I had never created a body of work without Pimp C’s partnership. So there were a lot of different changes I had to go through—finding music, finding collaborators, figuring out which songs worked and which ones didn’t, and how to traverse this new landscape from a solo aspect. So we had a lot on the line, but it was deeper than just me. You know what I’m saying? My thing was, if I failed, not only do I fail myself, but I failed my brother.

So the decision to create a solo album, was that a collective decision between you two?

Well, I mean, I never wanted to be a solo artist, but the reality was that the best way in my mind to perpetuate everything was to attempt to do a solo album. I never wanted to do one. I never had any aspirations to do one. I was in the best group in the world, so there’s no reason for me to do one. And we talked about it that at some point we would have different visions for ourselves. Super Tight. Many people don’t know this. Super Tight was originally recorded as a double album.

So one album was Pimp-centric and one album was Bun-centric. So we had clear ideas of as far as identity, and who we were collectively as well as singularly. But as far as moving into that space in that way, that wasn’t on the radar at that time. But Pimp as always had the utmost confidence in me. Nobody believed in me more as an artist than Pimp, ever. Maybe now that I’m married and I have a wife now that kind of comes almost with the job, but for the majority of my career, Pimp was my biggest fan. He was my biggest supporter, and he had full belief that I could do what I needed to do for this group. And so with that confidence, I put the team together, the producers, I put the engineer, my manager, my wife, we were all hands-on with this thing, and we put our best foot forward and gave people what we felt was a great album. And 20 years later, here we are still actively celebrating it.

Trill featured a Murderer’s Row of collaborations, for real. You had Juvenile, T.I, Jay-Z, Scarface; production from Mannie Fresh, and so on. How did it feel knowing that you could call up on damn near anybody for this?

Well, to be fair, Okla, I didn’t just call anybody and everybody–-these were calculated decisions. I tried to get as many producers involved with this project that not only understood UGK’s sound and understood Pimp’s production, but could keep me in pocket in a way. I wasn’t bringing people in to recreate what Pimp was doing. I needed people to give me music that worked for me. These were very concise decisions. I was like, I need Mannie Fresh, I need Jazze Pha, right? These guys know they make music for Southern people. They made hit records for the same people that we make music for. So it’s just about humbling myself and reaching out to people and asking for help. The beauty of it was that everybody loved and cared about Pimp C in the way that I did and wanted to see the group continue. So everybody that I reached out to understood the assignment. Many of them overdid, actually. I asked Mannie for a beat, and he gave me two.

So people overperformed for me on this project, and I felt the need to have to live up to that. So again, we gave it our best effort. We put out the “Bat Signal.” We got some great collaborators who also gave us their best effort and execution was as high as we could have asked for. The reception from the songs was exactly what we hoped for, and it really hit.

It’s a classic.

It exceeded all our expectations, I can assure you.

So talk to me about your Trill Unplugged performance in Houston, and why did you decide to align with Crown Royal on this?

Because there were a lot of things on the line. To be fair, Okla, there was a lot on the line in terms of the way we were going to present this album, the order of its storytelling, and bringing in different performers from the album. There were a lot of things that we had to worry about and try to compartmentalize to make this work. Having a company like Crown Royal supporting you helps to alleviate a lot of that stress, right? It takes a lot of anxiety off your shoulders because I don’t have to sit and worry about every single thing. They come in, they help compliment us. They take care of maybe 40 to 50% of the things that we need to build out the room and make it comfortable for people and make it easier for them to receive what we’re giving. And I can just sit with the band and worry about the show.

That’s the beauty of it. I just want to make sure I give people the best performance possible, but the way my mind works, it’s hard for me to just focus on one thing without worrying about a bunch of other things that are happening. Having this kind of a partnership allows me to not have to worry about it. This is not our first rodeo—no pun intended—but we’ve been working together for the last four years during the Rodeo, during performances, at the Rodeo, doing dinners, creating clothing capsules, and all of these different activations that are all authentic.You know what I’m saying? Because it’s just a deeper way of connecting with the community. That’s what we’re about. That’s what Crown Royal is all about. That’s why the partnership works, and it fits like a glove. We know at the end of the day, we both want the same results.

As far as performing live, you’ve been doing it for a long time. Is it still as invigorating as it was when you first started?

I get nervous before every show. There’s no way around it. There’s no way around it because I want to project the best version of myself every time I get on stage. I don’t want to miss a word. I don’t want to miss a cue. My biggest fear is dropping the microphone or falling down.

It’s still fun, but I have to be honest. I’m getting older. The fans get older and they get younger. It’s crazy. So I’m used to seeing a bunch of my contemporaries. Guys, let’s say, graduated around the same time I graduated to make it easy, right? It’s good to see those people still come out to the show, still appreciate the music, and then every now and then you’ll see somebody bring their son, bring their younger brother, bring their nephew; or somebody brings their dad. And they all get to become a part of this experience and it becomes a shared experience for the family.

I’m honored to be able to create moments like that for people. That’s the beauty of doing this job. It’s not about getting up there and getting in front of people and having levels of praise and picking up those backends. All of that stuff is cool. But to be able to create something singular for people in the crowd that goes with them, every time they hear their song, they think of that moment, it marks a memory for them. That’s the residual benefit that I love to receive from doing what I do.

What does the word “trill” mean to you?

“Trill,” from where I’m from—Port Arthur, Texas—has always been a part of the lexicon. It’s always been a word that we’ve used to identify each other in spaces and to separate ourselves from other people. So, when you walk in a room of mixed company or something like that; we would just yell, and somebody else would respond. With that, we would know that other people from Port Arthur were in the room. So when we started creating music, “trill” was just a word that we used every day. So we put it in the music, and for a while people didn’t really understand it, but they could draw the context of what we meant—and that was good enough for us. Now, if I had to explain it, being “trill” or “keeping it trill” is about going above and beyond what people would normally do when they keep it real.

It’s very easy for me to keep it real about you when you’re in the room. But when you’re not in the room and I’m in private, I can say anything I want to say about you, and no one would know. I still keep it real. That’s what being “trill” is about. It’s about overextending yourself. It’s about standing up in the gap for people that would do it for you, being who you need to be in the moment, even when no one’s there to hold you accountable.

Houston has always been synonymous with UGK. How do you feel about the city’s influence on you and just the support that the city has shown you throughout your career?

I was born in Houston. I was raised in my earliest years in Houston, and then I moved to Port Arthur in elementary school. I came back to Houston for graduation night. Basically the night I graduated, I came home, packed my shit, and I went to Houston. Houston has always been home. I’ve just found ways to work my way back to it. But once I came home after graduation, that was it. Houston was my home. I lived in Atlanta for about a year, but that was inconsequential.

The level of peace, the level of community, the quality of life, the lack of burden of having to traverse a city full of criticism. I don’t think any city on the planet treats their local heroes like Houston—whether it be an athlete, a politician, a musician, whoever it may be. I don’t think anyone holds those people in high regard and treats them better than the people of Houston. I’ve never felt uncomfortable. I’ve never had to deal with people looking at me a certain way or feeling a certain way about me. They’ve always made me feel welcome. They’ve always given me praise. They’ve always lifted me up. Here’s the beauty about Houston. Houston knows when I’m up and they know when I’m down.

So when things are good, people are like, “What’s up, OG? I see you doing your thing right now.” And then when things are bad, people are like, “OG, I just want to tell you, we are thinking about you, and we are praying for you.” I couldn’t ask for anything better than that, and I’ve been to other cities. I’m in New York right now, and there’s a certain level of reverence that I believe they just don’t give to people that deserve it. I think there are a lot of amazing artists and musicians and rappers and producers from this city that should be getting more admiration, should be getting more praise, should be getting more support. But this city, this is a big city, millions of people, and it keeps moving. Like New York doesn’t stop for anybody, but Houston will pause. I don’t know if that’s really anything more I could ask for in that place. That’s the beauty of being in the city of Houston. I’m just in a beautiful space right now. I live in a beautiful place, Houston, Texas.