In 2020, the world was introduced to the remarkable story of Sibil “Fox” Richardson and her husband, Robert “Rob” Richardson, in the acclaimed documentary Time. A father of six, he was serving an unfathomable 60-year sentence at Angola Prison for his role in a bank robbery. Fox, who had served over three years for her part in the same crime, spent nearly two decades fighting for his freedom while raising their children. The film—told through Fox’s home video recordings before and during his time in prison, and original footage—chronicled their family’s life during this painful period. In 2018, after 21 years behind bars, Rob was granted clemency.

Time was a critical triumph. Director Garrett Bradley became the first Black woman to win the Sundance Award for directing in the U.S. Documentary Competition. The film went on to earn a Peabody and an Academy Award nomination for Best Documentary. Rob was finally home to witness it all.

But their story didn’t end there.

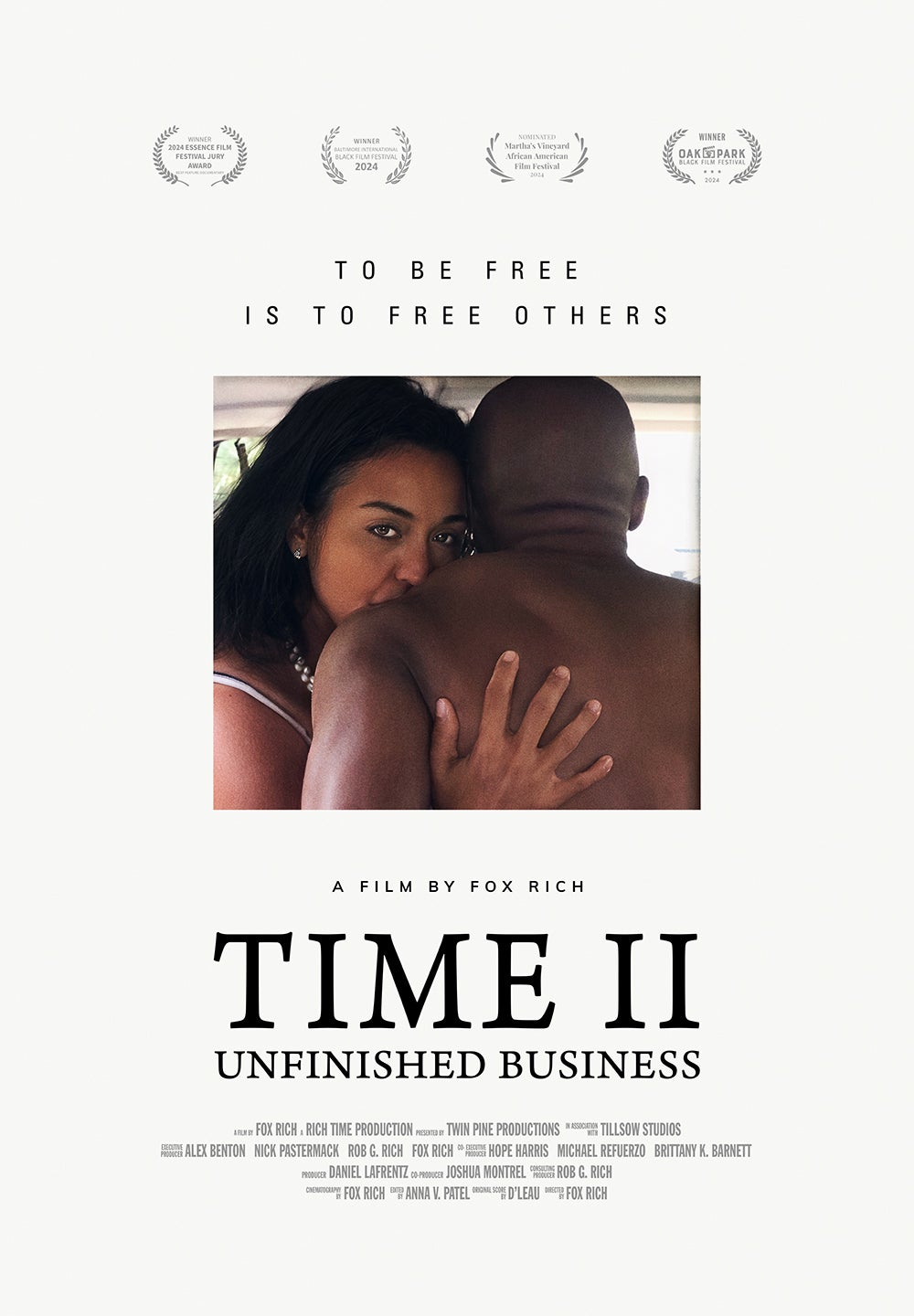

“Rob says, ‘Well, dreams just continue to come true,’ so I’m going to open with his line and say, ‘Dreams continue to come true,’” Fox shares over Zoom, Rob seated beside her. The couple sat down with us to talk about Time II: Unfinished Business, the next chapter in their story. While Time captured the pain of separation and the power of perseverance, the follow-up—directed by Fox—picks up after Rob’s release. It follows their joint effort to free his nephew, Ontario, who was also involved in the robbery, and expands to highlight their broader fight against unjust sentencing. Time II is set to release on June 19, 2025, which also marks Juneteenth.

“You want Juneteenth to be a celebration, a jubilee,” Fox says. “But because we’ve been so far removed from its meaning, we tend to think slavery is over. That’s the exception. And the exception is what pulls us back into it. Four hundred years of business is still unfinished—not just ours, but our people’s. Our business is unfinished because we still have slavery as an option for those who would tend to oppress.”

And as Rob adds, if their story feels like an outlier, “keep living.”

“Incarceration in this country can touch any family,” he says. “Live long enough, and it might be you—or someone you love. When that happens, you need to know how to navigate it. That’s what Time II offers. It’s a guide. One of those ‘in case of emergency, break glass’ kind of films. So if you find yourself challenged with the criminal justice system, and you thought that none of this would ever happen to you, we have a toolkit to help you.”

We spoke with the inspirational pair about life, love, and fatherhood after incarceration, and why Time was never the end, but only the beginning.

ESSENCE: What motivated you to want to go back in front of the camera to share this next chapter in your journey?

Fox Richardson: I thought it was amazing how people resonated with our story, and I was so very grateful. Even the concept of Time itself was Rob’s idea. We thought that it was going to be the only way that we were going to be able to get from under being condemned to die in prison, to be able to get from under this practical life sentence that Rob had been rendered, he and his nephew, was if we raised our story on a national stage. I’ve been working for decades talking to lawmakers, talking to this person and that lawyer and all, and nobody ever seemed to have any answers as to how I could undo this harm that had been done to our family through the state-sanctioned sentence. Rob suggested that we do a documentary, and I came back to New Orleans and started trying to see how we could even begin with this. And as you know, when you’re doing the next right thing, God puts what you need on your journey.

And it was in that moment that God sent Garrett Bradley to me who was working on another project for The New York Times. She asked to interview me for that project, and I asked her if she would go back and ask The New York Times to tell our family story, that I’m working to bring this story to light, and if she would help with that project. And so, Time was supposed to be a 15-minute doc on The New York Times website to help raise awareness about Rob’s excessive sentence in hopes that we could get him home, and instead, what God intended for it was something totally different.

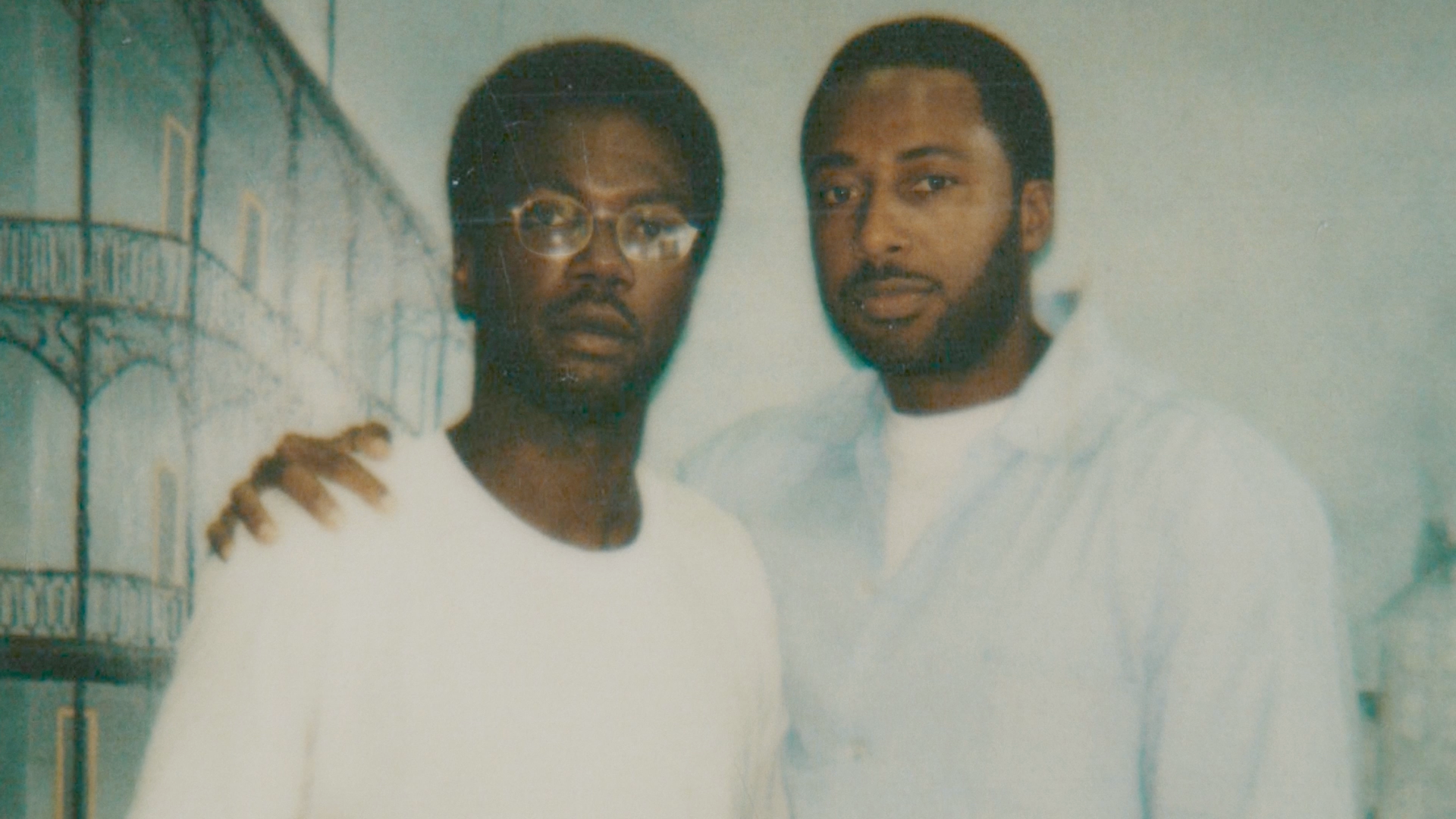

And so, for me, knowing the stakes that lay ahead of us with what we were commissioned to do —meaning that we had left our nephew behind, who was our fall partner —and we invited him to participate in this behavior with us. And so we had a duty and an obligation to unfix for him what we had unfixed for ourselves. So the plan was that I had the lesser amount of time in prison. I would come home, and I would work to get Rob home, and then once Rob came home, we would work to bring our nephew home.

And so I wanted to be able to show people two things. One, how Rob actually got free because Time doesn’t tell you how we secured our freedom. And with the people that we serve, the families that we have been with for the past 30 years, we know that we need to know the tools. How did that happen? It wasn’t magic, and why did it take 20 years? So I wanted to answer the whys that people who love Time wanted to know, and then I wanted to be able to show them what we did with freedom after it became ours. What we understood was that to be free is to free others. And that is what we were hopeful to show with this film and give back to folks.

Got you. And why was it also important, this time, for you to be behind the camera as the director?

Fox: Oh, because I ain’t had no money to pay nobody else. Necessity is the mother of invention. And then when you think about it, Time actually was comprised of almost 70% of my archive footage.

Yeah, that’s right.

Fox: And so when you think about that, I had been directing, not in titles, but in necessity. We as Black women, we’re directors, we direct our families, we direct our community. And so it’s just a natural course of things.

Got you. And you were married for a brief time before you both faced incarceration. I know Fox, you had three years, and Rob 21 years. How has it been adjusting to actually being together since his release?

Rob Richardson: When you said that we were married briefly, that was definitely putting it lightly. We were like 180 days on the other side of exchanging our nuptials. But Fox and I do have 10 years of an on-again, off-again relationship with one another that predates our getting married. But we’ve also been in a long-distance relationship before, when I was stationed in Holy Loch, Scotland, when we first met as a couple. After two weeks of me being home on leave, I went back overseas, and then by being overseas, we maintained a two-year relationship for the most part with each other at a long distance. I don’t know if that was preparing us for what was going to come later or not, but you definitely have a way of utilizing things that your life experiences have taught you over space and time to help get you through whatever your moments are in the present time.

But the day that I walked out of prison, it was probably in that moment when both Fox and I came to the realization that what we had both been hopeful for as it related to our encounters with one another, they were slightly different. Fox had spent 21 years looking for the day that we would be together and be in bed together and be in the shower together and doing all the things that lovers do, right? At the same time I had spent my experience caged in a place with more than 6,000 other men. My bedroom or the dorm where I lived, they had over 100 men who occupied the same space that I did. What that looks like is when you look at one of those topography views of the old slave ships, where you are head to foot. I had managed to live that way for more than two decades.

So by the time that I came home, I wasn’t necessarily looking to share my bed with anyone because I’ve been attached to a bed with someone else and every time he moves at the bottom or somebody moves on the side of me, I’m alert. I’m waking up because I’m not in a deep sleep, because I also live my life on alert in an environment like Angola Prison. I shower alongside men all day long when the showers are rolling because it’s 100 of us that got to get in there. Ain’t never a moment that it’s going to be open. I was not necessarily looking to take a shower with anyone else. I was just glad I could even close the door behind myself without being under surveillance.

Those moments, they clashed with moments for Fox and I. We were now starting to be able to feel what life was like for the both of us and we realized how much pain each of us had been through, but different types.

And so that brought about its own set of challenges. The film production team that was there for our first film, Concordia’s Davis Gubenheim, was generous enough to acknowledge that we had been through something and, as subjects of the documentary, paid for counseling for us. And it was the first round of counseling that we went through. We realized that not only did we need marriage counseling, but we needed individual counseling.

Yeah.

Rob: I suffer from PTSD, Fox suffers from no man in the house SD.

Fox: Abandonment [laughs]. Boy, you are crazy.

Rob: But it’s just all those things. And I’m trying to figure out how to mesh these two individual lives that have been through hell and high water.

Fox: Real hell. Hell, hell.

Rob: Right. Real high water. Katrina kind of water. Just in those moments, like I said, we’ve had a number of challenges. I’m just hopeful as Fox mentions in the first film, that she will ultimately get to a point that she is so far on the other side of this experience that she’ll fail to remember how bad it hurt. So it is in this moment that we’re working past, we’re hopeful that enough time will pass, that we will be able to move past our hurt, and we’re not there.

Something that was poignant that you noted, Fox in TIME II, was that you also needed to figure out who you are on your own. Can you kind of speak to what you meant by that?

As Black women, we are under so much pressure when we get here. From the time we come out into the world, it’s like, okay, figure it out quickly. And so, I had been so focused on making sure I could restore my family from this tragedy, this travesty that we had created with our own hands, just being unrelenting about making sure that in the midst of our low points, our children wouldn’t have to bear the brunt of what we had done. So that means I want to make sure that they’ve got a certain standard of living, that they’re all cared for and have their needs met so that they don’t feel how heavy this weight is that their family has taken on through our decisions. But trying to focus on being a good mother because that’s what we want to do.

And many of us really are, I would probably say fixated on doing a good job with no resources. And so that was my hand that I had dealt myself and the hand that I had been dealt. And so my goal was to say, he’s home now. He’s okay, so I don’t have to worry about him. These boys, they’re grown. I have done exactly what I needed to do. So the challenge is now taking all of that energy that you’ve given to others your entire life and now turning it toward yourself. And so I’m figuring out what that looks like for me and how I can just pour into other women the lessons that I’ve learned along this way, that we can overcome the hardest of obstacles and the rewards are on the other side if we’re just disciplined enough to make the commitments that we have to make in order to get to where we’re trying to go.

I love that. Rob, with Father’s Day this month, your sons have always been in contact with you, but, still there is this whole aspect of life that was going on without you. How do you find peace in this unique role of being a father now that you’re present in this stage of their lives as adults?

Rob: I stopped trying to create in my mind what I thought fatherhood is supposed to look like when you’re present. And my son, my youngest son, mainly because he was the one who was still in the house when I came home, as I relied on the older one when I went into prison, I was now having to rely on the younger one coming home. So he was my tutor. I taught him how to write because kids nowadays, they pick at computers and on phones and all that other stuff. So they really don’t know how to write anymore. I was able to teach him how to write, and we would start reading assignments with one another, but at the same time, he would show me how to work a cell phone.

But I think that my goal was just to let it all happen organically. While I was in prison, I traded my role as a father for a role as a coach. I had realized through a magazine that I read, that the average time a father spent engaged with their child was an average of eight hours a month. And so even while in prison, I had twice the amount of time of the average father if I maximized my visiting opportunities. So when I came home, I realized that even though prison walls were no longer putting us in a distant relationship, adulthood was now putting us in a distant relationship to one another. Them starting their own lives, has created its own distance. I started realizing that the only time they hollered at me is when they were in trouble. I’m the dude that they come to when they’re in trouble because they’re like, okay, if anybody knows trouble, this brother here knows trouble. But we’re building out from that.

But that is kind of how I think that it broke into me now being able to provide counsel to them in need, and then it being valued. But it stemmed from moments that they were having trouble in their relationships, if they were having trouble with their time on the job, just all the things. And like I said, just in those moments, I think it was the gateway through which we were able to really kind of start interacting with one another. So, just for me, fathering has continued to be about coaching. It’s the next level of coaching for me right now for them.

Obviously, Juneteenth is honored as a celebration of freedom. Knowing the messaging in this film and the ongoing work that you’re doing to expose the unjust sentences that are imposed upon many Black men and women in this country, why was this the perfect time to release this project?

Fox: We didn’t want to expose this system. We don’t have to expose this system. Everybody knows this system.

That’s true.

Fox: What we were intentional about doing with this film on Juneteenth is empowering the people. I wanted them to see us fighting and winning and fighting and winning and fighting again and winning again. That is what this release on Juneteenth is about. They didn’t give us our freedom. We fought, we bled, we died. We were unrelenting about our freedom. I just say that it is about making sure that they take this film and this moment and know that there is nothing we can’t do together.

“To be free is to free others,” as you noted. That’s the overall message behind this project. This film signifies that there is work to be continued. So what do you say to people who may miss the humanity of individuals who are incarcerated and say, Oh, you do the crime, you do the time and not realize there are really just some very atrocious sentences that are imposed upon people?

Fox: I wouldn’t say nothing. When you think about the fact that one out of two Americans, not White, not Black, one out of two Americans has a loved one incarcerated. One out of three Americans has a felony conviction or a loved one with a felony conviction. When you talk about the current president having 34 felony convictions, the outgoing president’s son being pardoned on a felony conviction, it’s in the very fiber of America. And so all I can say is that you don’t have to get it now. You’ll get it in the buy and buy.

Rob: And then just looking at some recent stats, with all of the crimes that are actually on the books as American people, we commit an average of three felonies a day, unintentional. So the people who say stuff like that, you are committing felonies every day. It’s just that for whatever reason, they’re not targeting you, they’re not necessarily focused on that particular offense. But on a day-to-day basis, we’re breaking laws that we don’t know because they got thousands of them on the books. We focus on murder, robbery, rape, drug dealing, drug selling. But there are so many more. I mean, I’m talking about literally, there are thousands of offenses that qualify as felonies. So, to a person like that, as Fox may mention, you don’t necessarily have to bother saying anything to that particular person, but just sharing those types of facts, the thing that you have to know as a person who would take on that position is that your time just hasn’t come yet. Just keep living.

Lastly, what’s next for you both?

Rob: Time III. Because again, our business is still unfinished. I’m on 40 years of parole right now. I still have to check in. And in the film, like I said, it’s like going from slavery to sharecropping. So somebody is still telling you what to do. You’re still having to ask for a request to go from one plantation to the next, one state to the next, in my instance. But all of those things are still very much in place. I’m still under supervision. My property, my space, and all of that can still be subject to shakedown.

It will be 28 years this September since this offense happened. And so with that being said, I think that I have satisfied the purpose for punishment, and I think that it’s time for those in authority to know that that time has come. And I’m asking them, respectively, to do the right thing as it relates to me and my family, so that we can at least pick up with what’s left of our lives, just out of human dignity and respect. That is the next chapter, or the next wave, of our life right now. And we’re still recording.

Visit timetwomovie.com to watch the film on Juneteenth, to partake in live stream discussions, and to find the toolkit to be empowered.