This story is featured in the July/August 2025 issue of ESSENCE.

Rae Lewis-Thornton was diagnosed with HIV when she was 24. The year was 1987, a time when the epidemic was accelerating at an alarming rate. Two years prior, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) had found that 51 percent of adults and 59 percent of children whose HIV had progressed to AIDS were dying of the illness, often within 15 months after learning that they had the disease.

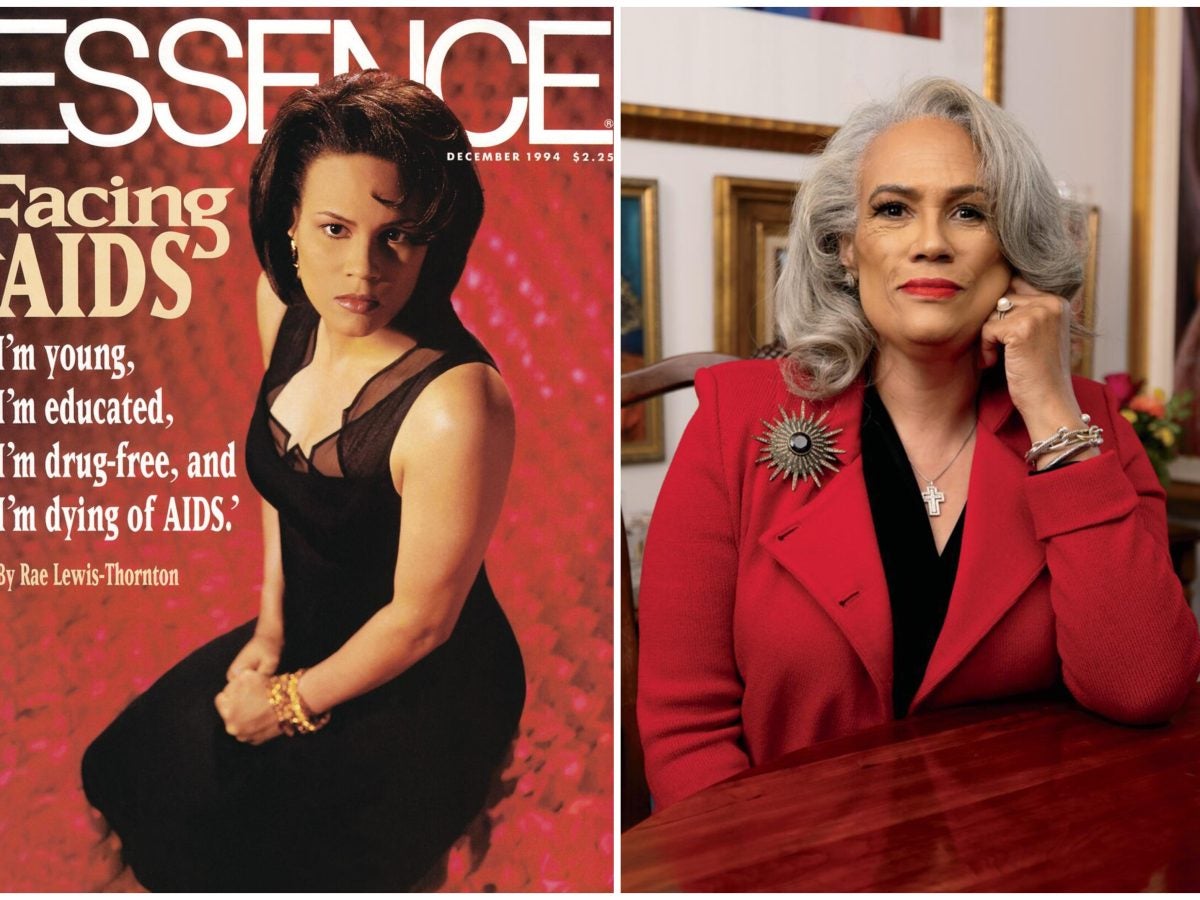

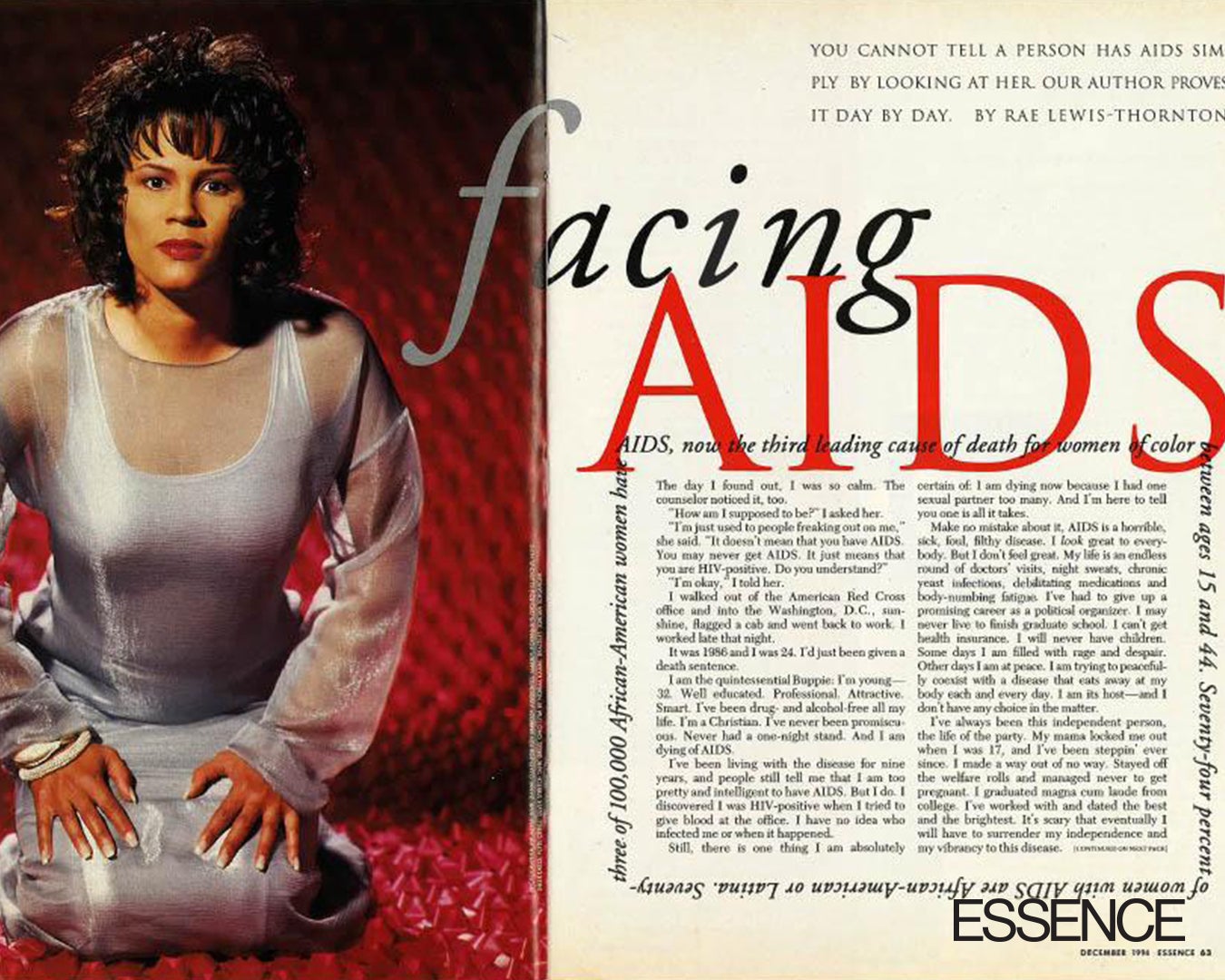

In 1994, 32-year-old Lewis-Thornton appeared, stoically, on ESSENCE’s groundbreaking December cover—boldly declaring that she was “Facing AIDS.” In her interview with Teresa Wiltz, she shared how an attempt to donate blood led to discovering she had HIV, which by 1992 had become full-blown AIDS. An educated, accomplished Black professional from Chicago who had survived an abusive childhood and seemed the picture of health, she stated simply, “I am dying.” She seemed serene about and settled into her presumed fate, yet she resolved to keep living fully. And more than 30 years after she put a Black woman’s face to the HIV crisis, Rae Lewis-Thornton is not in a grave. She’s living, happily, in the small town of Alton, Illinois.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, Lewis-Thornton decided, I am buying a house, where I can have my morning tea and listen to the birds chirp. She was done with doubt, fear and apartment-living in Chicago. Today, the walls of her beloved cottage house—more than four hours Southwest of the city—are covered with watercolors, acrylics, religious imagery, florals and portraits she’s been collecting for three decades. At every turn, she sees something beautiful that helps her stay on an even keel, emotionally, while living with AIDS at 63. “I’ve never been more at peace in my entire life,” she says, “than I am now.”

No longer married to the man she introduced in her ESSENCE story— “I ain’t seen that Negro walking on the street, literally, in twenty-something years”—she embraces her solitude.

“Honestly, I’m good. If I don’t see another penis in my life, I’m good,” she says, recounting abuse from childhood and complicated relationships as an adult. “Now I want to garden. I prefer to garden than to have sex.”

Surviving all these years has been, without question, a triumph. But it has also been hard. Lewis-Thornton has weathered three bouts of the AIDS-related infection Pneumocystis Jirovechi Pneumonia (PJP), which has claimed many lives. She has lipodystrophy (abnormal distribution of body fat) and osteopenia (bone-density loss), and she’s fighting high cholesterol because of the medication she is prescribed. She takes antidepressants—because “I believe in God, but I also believe in science”—and has medicine fatigue, from taking pills and getting injections for the last 30-plus years.

Missing a few doses of her medication recently—“four pills in the morning and three at night”—caused Lewis-Thornton’s viral load to become detectable again at the time of our conversation. When HIV is undetectable, the virus is under control and can’t be transmitted. But when it’s detectable, the immune system is vulnerable—opening the door to opportunistic infections. This is living with HIV/AIDS long term.

“I’ll always have HIV in my body, because there’s no cure,” she says. “There is always inflammation when there is a foreign agent and your body is trying to fight it off. So we have a higher morbidity with issues of cancer, heart disease and diabetes than people who are aging without HIV.”

Even though a diagnosis of HIV or AIDS is no longer the death sentence that many feared in the 1980s and 1990s, Lewis-Thornton maintains that “the best advice is, don’t get infected. You can live a long time, but your body is internally aging. HIV is not just in my blood. It infects all your organs.”

An Ongoing Crisis

Overall rates may have decreased, but a lot of people are still contracting HIV—especially Black women. According to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services’ Office of Minority Health (OMH), in 2022, Black women were 10 times more likely than non-Hispanic White women to be diagnosed with HIV. Black heterosexual women fall behind only Hispanic/Latino gay men, Black gay men and White gay men in diagnosis rates, per the CDC. Even more disturbing: Young people 13 to 24 account for 20 percent of new HIV cases in the U.S.—and they’re the least likely to stay in care. The reasons behind these troubling numbers are complex.

“There are young people I’ve spoken with who don’t even know what HIV is,” says Bithiah Lafontant, 44, Director of Corporate Communications at ViiV Healthcare, a global pharmaceutical company that develops medication to prevent and treat HIV/AIDS. “When I was growing up in the 90s, HIV really was something that people thought about.

“It was prevalent, in the headlines—like the ESSENCE cover in 1994,” continues Lafontant, who is based in Raleigh, North Carolina. “I think HIV, even 20 years ago, was a bigger part of the discourse than it is right now.”

This lack of education affects everyone from teens to older adults, who sometimes engage in unprotected sex in nursing homes. “I’ve been in settings where people say, “Condom? What is that? Why use it?” says Maisha Standifer, Ph.D., M.P.H., Director of Population Health at the Satcher Health Leadership Institute at Morehouse School of Medicine. The community-based researcher, 51, has been trying to inform people since she was at Spelman College in the early 90s, dispensing educational materials and condoms at Atlanta’s Freaknik parties. “When you’re in a relationship, whether it’s committed or casual, you need to use protection prophylaxis. And that’s including condoms.”

In addition to such highly effective barrier methods of prevention, there are newer medicines—like pre-exposure prophylaxis, or PrEP, and PEP for post-exposure protection. However, many people don’t think they need them. “Some say, ‘Okay, well, I’m not engaging in “risky” behaviors,’ ” Standifer notes. “But having sex, that’s a risky behavior.”

Lewis-Thornton agrees that too many people assume they’re not at risk. Some cisgender women, in the pursuit of relationships, forgo asking a guy to use condoms; some people avoid getting tested; and some see HIV as a simple chronic disease now, something they no longer view as a major concern.

“I tell women all the time, ‘If the penis it ain’t in your pocket, you have no idea what it’s doing when it ain’t with you,’” she says. “The only way to stop this disease is for people to really, really wrap it up.”

Protecting Yourself

PrEP, approved by the FDA in 2012, is touted as a formidable prevention option—as it reduces the risk of getting HIV through sex by around 99 percent. However, early marketing unintentionally reinforced the misconception that the product, and the virus, was only for gay men.

“A lot of people saw PrEP commercials and they’re like, ‘That doesn’t have anything to do with me,’ ” Lafontant says. “Black women are one of the groups most affected by HIV. So now we try to be inclusive in our marketing. Commercials today include different people—so everyone can see, That person looks like me. Maybe I should pay attention. HIV does not discriminate. We want to make people aware that there are preventive options for everybody.”

Even so, new drugs are often met with skepticism in Black communities, where there is a long history of medical mistrust. “It’s the same thing with COVID-19, whether it’s a vaccine or some other type of medication—culturally we’re saying we don’t want to be forced,” Standifer notes. “So whether you think you have reasons to take it or not, we’re still very apprehensive.”

Brittany “Britt” Williams, Ph.D., 34, of Atlanta, started using PrEP after she discovered that a former sexual partner had practiced “stealthing”—removing or damaging a condom, or lying about using one, during intercourse.

“This person was in school to become a medical doctor,” Williams says. “I decided to walk away. I could not rationalize, process or understand that even as someone in health care, he could not fully understand consent and the right of refusal. I agreed to have sex with him using condoms or a barrier method. I did not agree to unprotected sex.”

Leaving that situation with her health status intact, she is now a vocal advocate for PrEP use. “There are broad assumptions that the only women on PrEP are those who are engaged in sex work, or they have to navigate sex trafficking, or they are having promiscuous sex,” she says. “I want to reshape the narratives around what a PrEP user looks like. It’s for everybody.”

Doing the Work

Gracie Cartier, 46, of Los Angeles, is a trans woman, an activist and a host of Plus Life Media’s What’s the Jeuge talk show. Diagnosed with HIV in 2003, she has been using her platform to end the stigma around it. A former star hairstylist who worked with Garcelle Beauvais, Tia and Tamera Mowry, and others, she decided to share her diagnosis publicly in 2021 and to embrace her truth.

“I’m a person who has been through so many different painful, traumatic experiences,” she says. “But there’s purpose in everything that we go through.”

Cartier’s hardships included sexual abuse, molestation, losing both her parents and surviving gun violence—twice. Such trauma plays a significant role in HIV diagnoses, and therefore it must be addressed in order to curb new infections. “Trauma leads to risky behavior,” Lewis-Thornton explains. “I told my mom her husband was touching my breasts, and she said, ‘You ain’t going to f–k up my sh-t.’ Being beaten, sexual abuse in a family—it really impacts who we are, what we do and how we move.”

Cartier agrees. “It plays a huge role in the way that you see yourself, your self-worth and your value, and that can lead you on a path that may be self-destructive,” she says. “You may not feel that in that moment, because it’s deep-rooted. But as you grow and heal and become more honest with yourself, you see it does play a part in your decision-making and how you ended up in the situation you have.”

Thinking it couldn’t happen to you is naive. “Never say never,” says Cartier. “Sometimes the things you feel would never happen may be a wake-up call for you. Be mindful, be aware, be proactive.”

Having worked through her traumas, she encourages others to live authentically—all stigmas, HIV included, be damned. These days, she refuses to allow her diagnosis to hinder her joy. “The diagnosis does not define me. I’m so much more than that,” Cartier says. “I am a bright, beautiful, colorful human being. It’s taken a long time for me to say that—not from a place of ego or pride, but knowing that all of what tried to break me down has only built me up.”

Lewis-Thornton also spent years doing the work, processing the trauma that she experienced, at the same time as she made her efforts as an HIV activist. Today, with Black women still at a disproportionately high risk of becoming infected, she says that her work is far from over. As she continues to fight for her life, Lewis-Thornton reflects that her decision to speak out 30 years ago was just the beginning.

“I still do the work, because my life is my ministry,” she says. “Susan Taylor heard me speak for three minutes, and she called me two weeks later and asked me to be on the cover of the magazine. I said, ‘Why would you choose me? I’m a nobody.’ She replied, ‘I believe you have a story to tell.’ She saw something in me, and I appreciate that. We did what we did back then, and it was a good thing. But it’s not over yet, because people are still dying from AIDS, and most of them are Black people.”