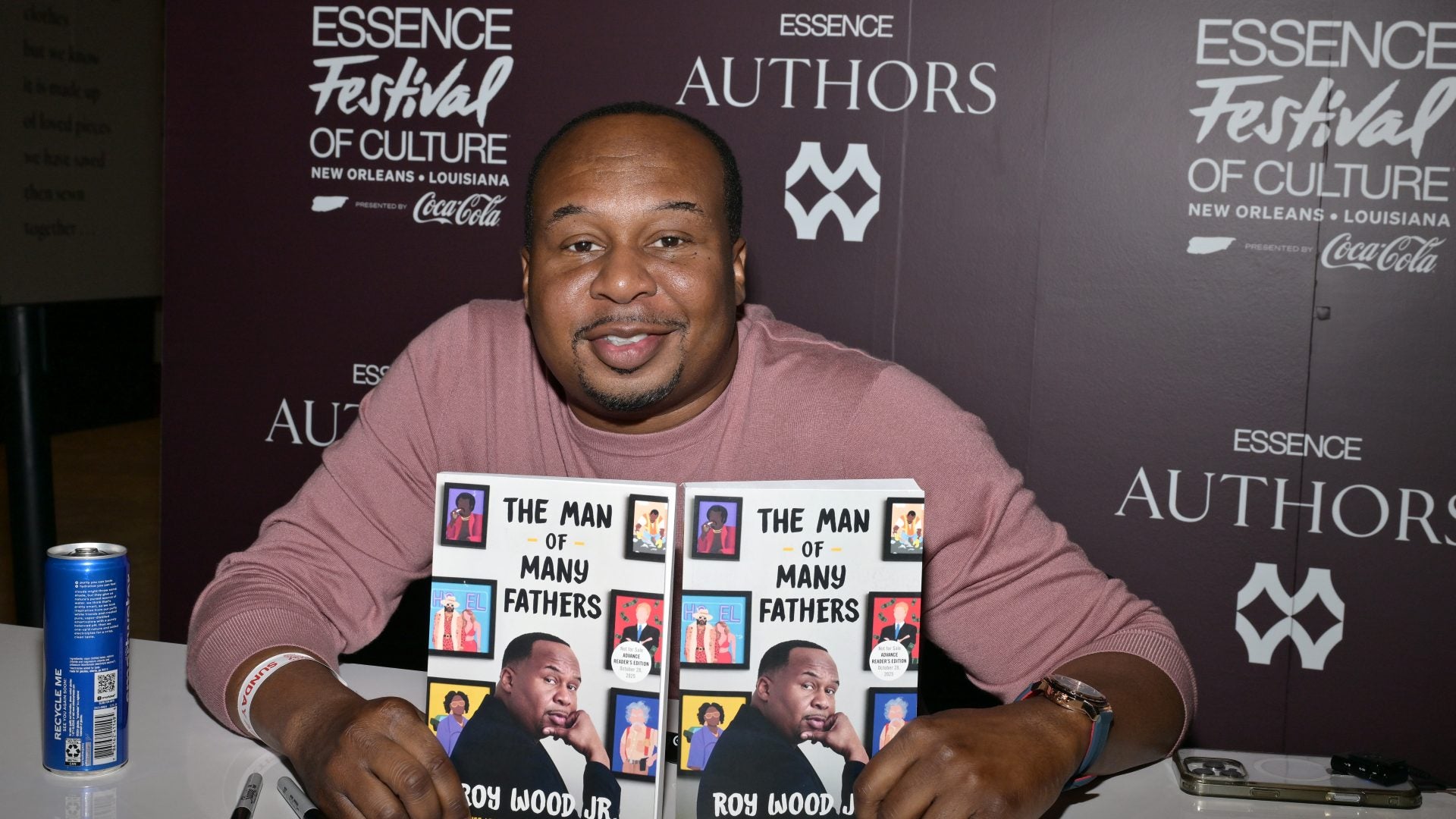

Actor and comedian Roy Wood Jr. traded his mic for a pen with his new memoir, “The Man of Many Fathers.”

The conversation took place during the 2025 ESSENCE Festival of Culture on the ESSENCE Authors Stage, where Wood sat down with Okla Jones, ESSENCE’s senior entertainment editor, for a candid and humorous discussion about fatherhood, legacy and healing.

Wood said the book was inspired by the death of his father when he was sixteen and his journey to define the kind of father he wants to be for his own son. His goal in writing, he shared, was to document the invaluable lessons he learned from the many male mentors life brought him.

“As a Black man you have this sense of mortality,” says Wood. “You never know when it’s coming but the idea of my son having to exist with that same deficiency and my absences should I pass before he’s old enough for me to give him the game personally.”

Forty-four percent of Black men live apart from at least one of their children — the highest rate among racial groups, according to the Pew Research Center. That stark reality, Wood said, was part of what compelled him to write the book

Among the lessons Wood discusses are the importance of healthy communication, the role of community support and the insights drawn from his own complicated relationship with his father.

“You have to teach your children about consequences. It’s consequences to actions,” says Wood. “The idea that my son is doing something solely because he’s scared of me, negates his ability to understand the value of it at the moment.” Wood said he hopes that explaining consequences helps create healthier communication—and moves away from the notion of “do it because I said so.”

While praising his father’s professional accomplishments, Wood is honest about their personal challenges. Roy Wood Sr. was a pioneering Black radio journalist, civil rights activist and entrepreneur. Many Black media professionals from the 1960s to the 1990s worked with or were hired by him.

One notable story involves Don Cornelius, who—before creating and hosting Soul Train—was a police officer in Chicago. He once pulled over Wood Sr., who complimented Cornelius’s voice. “He pulled my pops over [and] my pop said, ‘You got a nice voice.’ And Don said, ‘That ain’t gonna get you out this ticket,’” Wood said, laughing.

As a native of the South who grew up during the Jim Crow era, Wood Sr. carried a more serious tone, shaped by the harsh realities of being Black in America. Wood acknowledged that he benefited from his father’s sacrifices and early exposure to difficult conversations about race and activism.

“I care about the same issues. I still wanna fight for the same causes,” says Wood. “But for me it was important to figure out how to make it funny, to give it an entry point so that some people may want to listen.”

Becoming an author, Wood said, pushed him to lead with authenticity over punchlines. Though it was an adjustment from his comedic background, he said vulnerability helped him form a deeper connection with readers.

“Everything else I’ve ever done professionally, the first objective is to be funny. You can be informative and you can speak about the issues,” says Wood, reflecting on his time at The Daily Show, where he tackled serious topics like gun violence through comedy.

During the writing process, Wood asked himself a difficult question: “When have I seen love?” The answer led him to reflect on the mother of his siblings. He recalled the pain of watching his father be more present in their lives, while he and his mother struggled financially. At a young age, he learned the value of money by sweeping parking lots in exchange for food and candy he later sold to classmates.

“My little brothers during Father’s Day, they post pictures of them and our dad on the old school Polaroid joints, they got the date at the bottom of the picture. I can look at the date of a photograph that my two little brothers posted with my dad and I can tell you whether or not the lights were on at my house,” says Wood.

Following the loss of his father, Wood turned to the men in his community for guidance, creating what he called “unexpected classrooms.” From laborers on job sites to comedians like Lavell Crawford and D.L. Hughley backstage, each encounter became an opportunity to absorb wisdom.

The central message of “The Man of Many Fathers” is clear: Even in the absence of a biological father, there is a path to learning—and becoming—the parent you needed.