This story was originally published in ESSENCE’s special 55th anniversary July/August 2025 issue, on stands now.

When ESSENCE magazine’s inaugural issue was released in May of 1970, it stood alone in affirming the boldness, beauty and brilliance of Black women. Since then, it has remained steadfast in that purpose, leaving an imprint on institutions far outside the magazine itself. In celebration of its 25th anniversary, the company launched what was then called the ESSENCE Music Festival. There, attendees from all over experienced the music, community and rich culinary scene of New Orleans—while also being immersed in the traditions of the diaspora. Susan L. Taylor, then ESSENCE’s Editor-in-Chief, championed visual artists in the event’s promotion. Thirty years ago, Black creatives began producing original works that blended their unique perspectives with the brand’s mission. Today, Taylor’s artistic vision has contributed to both the festival’s reach and the publication’s legacy.

For the first ESSENCE Festival in 1995, Willie Torbert was tapped to create the official artwork. His “Music Indulgence” presented a collection of Black musicians playing everything from brass to percussion. It was an aesthetic depiction of the fresh energy that pulsed through the fest’s earliest days. Created with a mixture of acrylic paint, pastels and markers, the piece signaled a milestone in Torbert’s career. Though he had long been renowned for his portrayals of Black expression, this commission carried new weight—especially since Torbert had never set foot in the Big Easy before that historic weekend.

“My mother and father were both from Alabama, and my uncle is from Mississippi—so even though I had never been to New Orleans, my Southern roots are deep,” Torbert says. “I knew that New Orleans was the birthplace of jazz, and I was familiar with its food and culture and everything, so I wanted to put something together that really represented that.”

Torbert was called upon again in 1996 for a follow-up piece, which he named “The Rhythm Within Them.” This marked another opportunity for him to interpret the philosophy of ESSENCE through his own lens—this time with a deeper understanding of the event’s audience. “It’s interesting because the work is a collaboration,” he says. “They tell me what they want, and then I hear that, and then I tell them what I can do, and then we agree upon that in the middle. That’s how it generally goes.” As Torbert understood, unity is what the gathering is truly about.

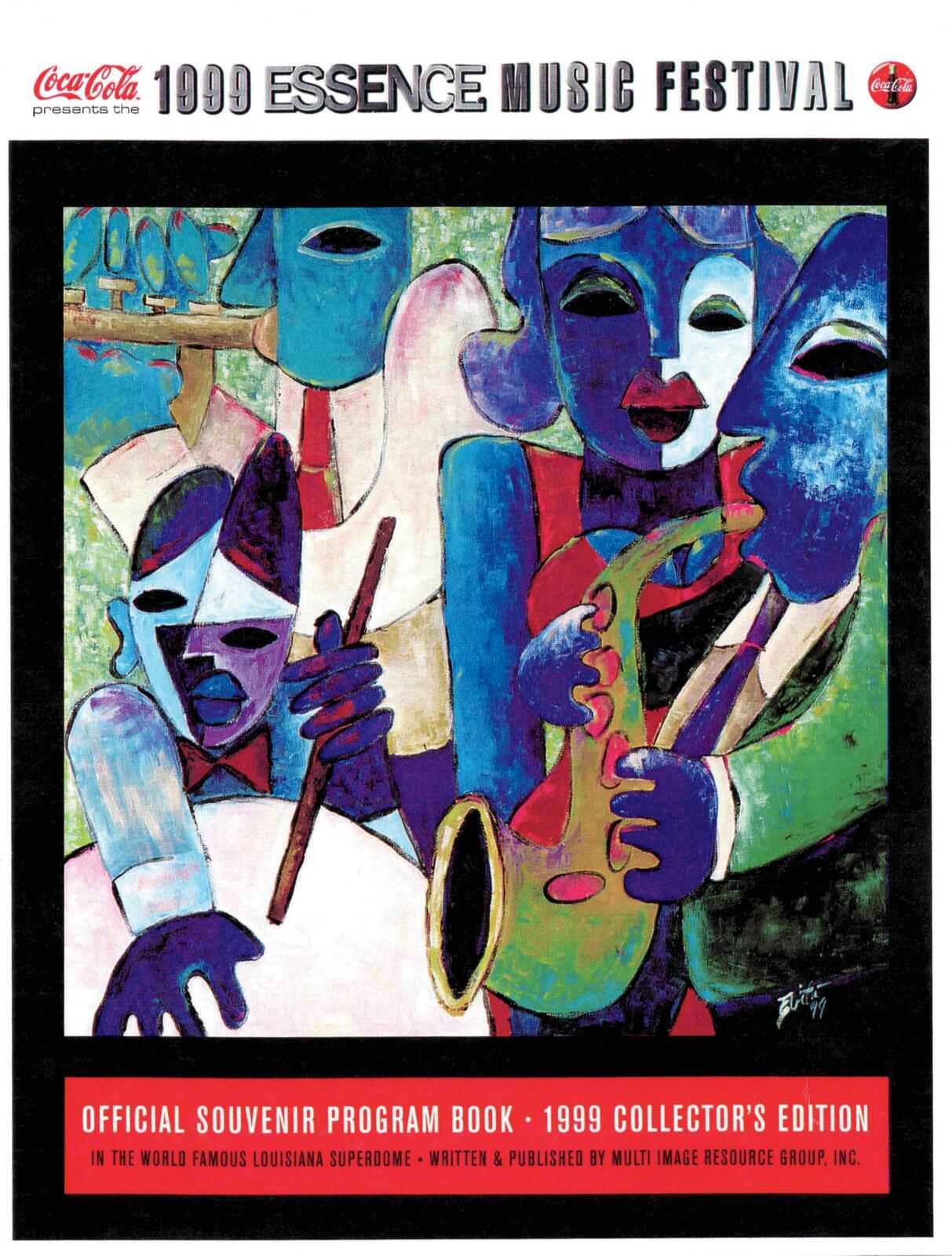

In 1999, Texas-based artist Evita Tezeno developed art for the festival’s fifth edition. The event had a star-studded lineup that included Lauryn Hill, Patti LaBelle, Erykah Badu and Maze featuring the legendary Frankie Beverly; any composition representing it needed to capture the spirit of Black music, as well as the heartbeat of the Crescent City. Tezeno had recently come to the attention of ESSENCE thanks to her “Congo Square” poster for the New Orleans Jazz & Heritage Festival, held earlier that year.

“The team told me that they wanted something along the lines of what I had created for Jazz Fest, but to push it a bit more toward music,” she explains. That direction, combined with Tezeno’s distinct prowess, led to “Big Band,” a piece featuring key elements of a quartet: the saxophone, the trumpet, the drummer and the singer. That work marked a turning point for Tezeno—in her practice and on the personal front.

“At the time, I was doing a completely different style,” she notes. “But I had a dream that an angel came to my front door and gave me a book of sketches for this new style, and the festival piece was the first one that I did with that particular style. ‘Big Band’ represents a new beginning for me. Doors were opening for me, and it was just so exciting.”

That sense of alignment between vision and reality only deepened once she arrived in Louisiana. “Everything that they wanted in the poster, I saw in real life,” she recalls. “I saw hipness. I saw women. I saw beautiful Black women. I saw all types of music, and I listened to all types of music.” The vibrancy she infused into this work struck a chord with the city, and Tezeno felt it. “When I met the people of New Orleans, they loved my poster,” she states. “They said that it embodied the true essence of ESSENCE, and they were excited to have that piece in their collection.”

Soon after its debut, what is now known as the ESSENCE Festival of Culture emerged as a multigenerational assemblage for people of color. By its 10th year, the affair called for something different; the commemorative artwork needed to be eye-catching, provocative and distinguished. Enter Margaret Slade Kelley, a seasoned artist whose emotive style made her the perfect choice for the moment.

Although Kelley’s “Creole Lady” was designed for the 2004 festival, the artist’s connection to the brand had begun long before. In 1995, her work had caught the attention of Taylor, who purchased one of her compositions during an auction at Sotheby’s and encouraged Kelley to send a full portfolio to the magazine’s New York City office. That introduction laid the foundation for a lasting partnership. Kelley was later commissioned for the 1997 event, and her paintings were featured prominently as the backdrop for the 25th Anniversary Awards telecast—an occasion that sparked national recognition and a surge in demand for her art. The significance of “Creole Lady” was not lost on its initial supporters and those invested in the advancement of Black art. In 2004, Chevrolet—then a sponsor of the festival—recognized the influence of Kelley’s work and invited her to speak about its meaning in a candid interview:

“‘Creole Lady’ is for ESSENCE, about ESSENCE—and ESSENCE means so much to so many of us,” Kelley said at the time. “It has mirrored us, so that we have the opportunity to see ourselves in a magazine…. It highlighted for us our points of beauty, and our points of intelligence, and our points of empowerment, and all the opportunities we have within that scope. So it was an easy visualization…. This is the 10th anniversary of the ESSENCE Music Festival, and if you live here, [you] know what that means. It means an absolutely marvelous experience for the entire city…. I love this city, and all its characteristics, and all of its culture…. I took the musicians, and I set the woman in the center point of the musicians, and I put them all in downtown New Orleans, with African fabric flowing in the background, just to represent the African-American experience.”

“The fine art served as a thread that bound creative disciplines, Rich with symbolism, these artistic narratives document the spaces where Black identity is understood.”

The inclusion of fine art in ESSENCE Festival’s promotional materials wasn’t just a choice—it was necessary for what was originally billed as a party with a purpose. It served as a thread that bound generations and creative disciplines. As ESSENCE grew, so too did the depth of the artistic narratives it cultivated. Rich with symbolism, these creations document the spaces where Black identity is understood. For Kelley, “Creole Lady” was a celebration of the company’s ethos, along with the soul of her then hometown.

“It brought people together,” Kelley says of what many call the biggest family reunion in the country. “It does it in a different way, but I believe it still does bring people together for a really unique experience. And I hope it never goes away, because we need that as Black people. We need that kind of experience and that kind of reminder that we are brothers and sisters. We are part of a community—all for one and one for all.” Her sentiments were echoed by Torbert, who also reflects on the festival’s impact. “It was always great to be out there,” he says. “Seeing all those amazing Black folks—it’s beautiful to know that the event is still going on today.”

The relationship between ESSENCE and visual art has lived on the publication’s pages. From its inception, when legendary photographer, filmmaker and author Gordon Parks served as the brand’s first Editorial Director, art has remained a pillar of the magazine’s identity. This legacy has only expanded over time: In the May/June 2021 issue, textile artist Bisa Butler became the first creative to grace the cover with a quilted portrait, unapologetically titled “Racism Is So American,” intimating that when you protest it people think you are protesting America. In the January/February issue that same year, a landmark collaboration with fine artist Lorna Simpson and megastar Rihanna yielded “Of Earth & Sky”—a 12-page portfolio of photographic collages that redefined modern standards of beauty. That stellar effort resulted in ESSENCE winning a coveted National Magazine Award for Photography from the American Society of Magazine Editors (ASME). And in 2022, Darius X. Moreno’s comic book–themed rendering of Angela Bassett proved that contemporary Black artistry could be both playful and profound.

Together, the magazine and the festival have built an aesthetic archive of love, resistance and belonging. From the canvases of Torbert, Tezeno and Kelley to the seminal covers that have been published throughout the outlet’s history, these moments expose a deep and enduring truth: ESSENCE has never simply reported culture; it has shaped and elevated it through exquisite imagery—through art.